![]() Download the PDF (1.5 MB)

Download the PDF (1.5 MB)

Abstract

In this paper I analyze how, in the Near East, the composition of pottery paintings changed with the advent of literacy. In order to make my case I compare and contrast compositions – the way designs are organized to decorate a vessel – before and after the invention of writing, ca. 3200 BC. I show that the former paintings consisted mostly of repeated motifs but that figures interacting in narrative scenes appeared among the latter. I conclude that, by borrowing communication strategies from writing, images could be made to tell a story. [1]

Introduction: Near Eastern Pottery Paintings Before Writing

Starting in the seventh Millennium BC, pottery decoration became a major form of art in Mesopotamia and Iran. The most common technique consisted of painting designs on the buff clay background of the vessels using a slip that turned red, orange, purple, brown, or black according to the firing conditions. Jars and pitchers were

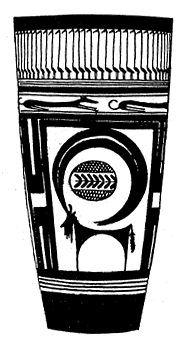

decorated on the outside and bowls and plates on the inside. Friezes filled the upper part of the high vessels leaving the lower part bare, (Fig. 1) while the interior of the flat vessels were covered in their entirety. (Fig. 2) The early Near Eastern potters drew from a wide repertory of motifs which included mostly geometric but also theriomorphic and anthropomorphic designs.

The Geometric Compositions

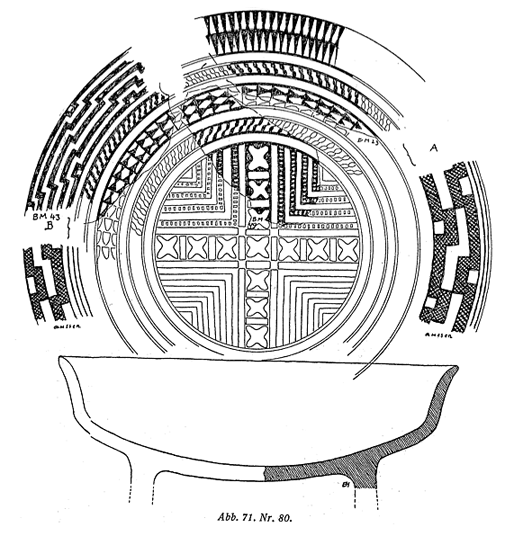

Geometric designs organized in multiple friezes constituted the most usual prehistoric vessel decoration. High vases featured several consecutive rows of varying patterns, and shallow vessels displayed concentric registers around a central motif. For example, a vase from the site of Samarra, Mesopotamia, ca. 5000 BC (Fig. 1) featured two rows of hanging triangles, followed by one register of herring bone patterns and a second one of broken lines.[2] In turn, Figure 2 illustrates the decoration of footed plates, also from Samarra, consisting of a cross-shaped central motif surrounded by four circular registers, each featuring rows of twisted lines, triangles and broken lines.

As a rule, each register featured one motif repeated as many times as necessary to go around the circumference of the decorated vessel. The repetitive motifs were drawn from a rich repertory which included circles, squares and rectangles, ladders, herringbones, festoons, checker-boards, crisscross, braids, vertical and diagonal bands, quatrefoils, swastikas, eggs and dots, and crosses, to name only a few. Among them, triangles were perhaps the most frequently used. They were treated in many ways; outlined, painted solid, or filled with stippling or crosshatching. Triangles were shown hanging, (Fig. 1 and 2) standing on end, attached in a chain pattern (Fig. 2), or doubled into diamonds or hour-glass shapes.

Lines, the simplest form of geometric design, played a particularly important role in the painting compositions of the preliterate period, where they were used in many ways. For instance, vessels might be decorated with a single line or sets of parallel lines highlighting the lip, the base, or the greatest diameter. Straight, twisted, wavy, broken and zigzag lines were also among the frequently used patterns filling the decorative registers. (Figs. 1 and 2) Most often, however, the lines were used to frame panels or registers of geometric, animal or anthropomorphic designs. Figures 1-2 and 3-4 illustrate how lines, either singly or in sets of 2 and 3, defined the space allocated to each of the motifs and clearly separated them from one another.

The Theriomorphic Compositions

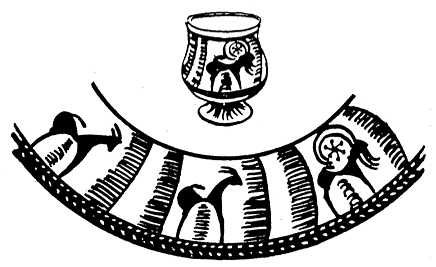

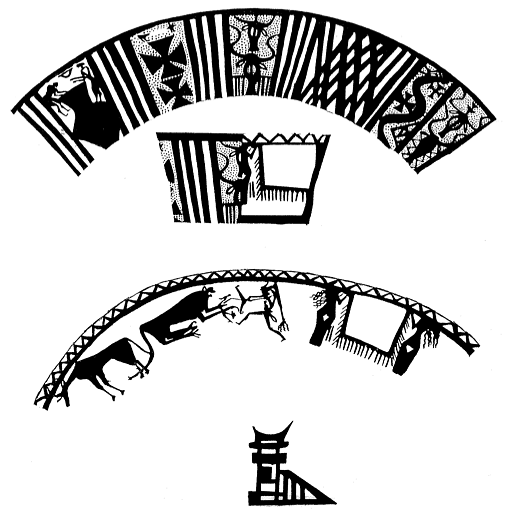

After the geometric patterns, the animal designs were the second most popular in Near Eastern pottery decoration, especially in Iran. Many animal species were represented on the vessels, including birds, fish, dogs, felines, bulls, deer, goats and donkeys. But, among them, the ibex, shown with huge sweeping horns, was by far the animal most often depicted. (Fig. 3-5) Occasionally a theriomorphic composition involved a single animal occupying an entire panel,[3] (Fig. 3) but more typically an animal was repeated over and over again to cover the circumference of the vessel.

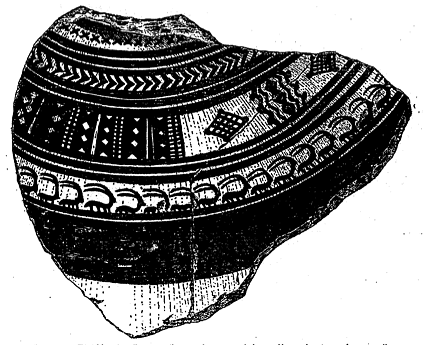

One of themost celebrated and most successful Near Eastern animal compositions of the preliterate period is painted on a remarkable tumbler from Susa, present-day Iran, dated ca. 4000-3800 BC. [4] (Fig. 4) The large goblet displays three different species: long necked water birds in the upper register, dogs in the center and ibexes, below. Thirteen lines of varying thickness structure the composition showing a great concern for symmetry. Note how the thick band around the lip echoes that at the base. The three lines below the birds correspond to a parallel set of three lines below the ibex. Finally, a pair of lines of different thickness appears in reversed order above and below the dogs to create a dynamic visual rhythm while the ibexes are boxed in dramatic frames. Often one animal frieze was just one element in a large geometric composition. As illustrated on a vessel from Moussian,[5] Iran, ca. 5000 BC, the line of ibexes, each identical to the next, was sandwiched between three registers of geometric motifs and an array of horizontal parallel lines of various thicknesses, either single or in sets. (Fig. 5)

The Anthropomorphic Compositions

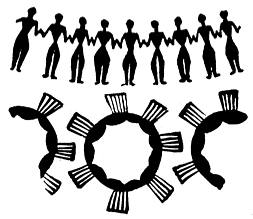

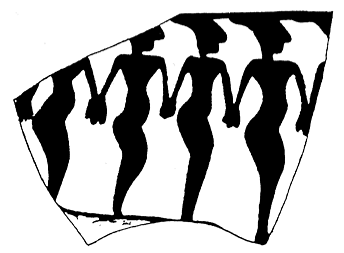

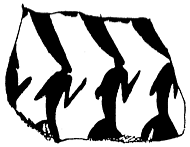

There are fewer vessels decorated with human figures than those with animal motifs. In other words, the anthropomorphic compositions appear least frequently in the pottery paintings of the preliterate period. Those extant followed the same principles as described above for the theriomorphic compositions, i.e., rarely one figure alone occupied a panel, but usually the same figure was repeated around the surface of the vessel as often as needed to cover the desired space. [6] As shown on Figs 6-8, the individuals were treated as silhouettes painted in solid color with the heads consistently lacking facial features. The figures were all identical, sharing the same size, position, and gesture. On a vessel from Moussian, the figures are shown frontally and holding hands like cut-out paper dolls.[7] (Fig. 6) On others, (such as at Shehmeh Ali,) the human form is presented in twisted perspective with the head and legs in profile but the torso frontal.[8]

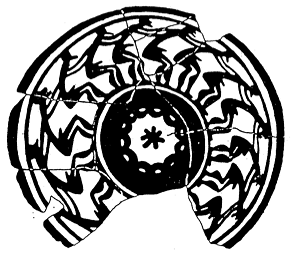

(Fig. 7) Lastly, at Tell Halaf, figures wearing high headdresses or hair styles follow one another in Indian file, holding their arms up.[9] (Fig. 8) A vessel from Tall-I Jari A, ca. 5000-4500 BC, illustrates that, like the geometric and the animal registers, the lines of repeated human figures were integrated into a geometric composition.[10] (Fig. 9) The painting depicts 16 nude, bearded men holding one another by the shoulders turning around a central star, surrounded by a festoon and a set of thick and thin parallel concentric lines. Here, the males are shown in profile placed one behind the other. The torsos and arms are oddly thin but the buttocks and legs are strong and muscular. Exceptionally the nose, a small pointed beard and the sex is indicated.

Figures shown interacting in order to illustrate an event are exceedingly rare in the preliterate period. Only four examples come to mind among the tens of thousand of painted vases of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods. Among them, two sherds from Halaf show two gesticulating stick figures too fragmentary to be intelligible.[11] The interior of a bowl from Susa, Iran, ca. 3500 B.C. features a hunter, sporting an impressive hairdo or headdress, aiming his bow at an ibex located on the other side of a set of sweeping broken lines.[12] The last and most unique example is a bowl from an unusual burial, located in an unusual context, at the site of Arpachiyah in northern Iraq.[13] (Fig. 10) The vase is generally assumed to belong to the Chalcolithic period, ca. 5000 BC, but the fact that one of the painted motifs is remarkably similar to the Sumerian cuneiform sign for EN = lord,[14] may well attest to a date after 3000 BC. (Fig. 11) The bowl features two small scenes on the inside of the rim and a third one on the outside. The first picture depicts a nude women sporting long curly hair, repeated a second time as a mirror image on the other side of a fringed quadrangle. In a second group, an archer tends his bow in the direction of a feline, while a bull walks away in the opposite direction. The third group includes two symmetrical figures climbing an enormous vessel. Whether or not they belong to prehistory, the vignettes of Arpachiyah and Susa involved a minimal number of predictable protagonists, such as a hunter and his prey or mirror and symmetrical images.

Figure 11. Sumerian sign for EN = Lord. After M.W. Green and Hans J. Nissen, Zeichenliste der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk, Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Uruk-Warka, Vol. II, Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 1987. p. 197: 134.

Characteristics of the Pottery Painting Compositions in the Preliterate Period

The innumerable compositions painted on potteries of the preliterate period share significant characteristics. Among them, the most remarkable is repetition. Geometric, animal and human motifs are repeated as many times as necessary to fill up the register to which they belong. For example, there are some 70 hanging triangles around the jar on Fig 1; 62 water birds are standing in the upper register of the Susa tumbler, (Fig. 4) five running dogs are juxtaposed in the next frieze, and three ibexes below. Finally, 16 identical men are pictured on the Tall-I Jari vase. (Fig. 9) Of course the specific number of triangles, animals or humans featured is not important since the purpose of the painter was only to cover the available space.

A second characteristic of the prehistoric pottery designs is the utmost stylization of the living creatures. The human figures are treated as simple silhouettes that do not reveal facial features. On the Susa tumbler, (Fig. 4) the long-necked birds of the upper register are reduced to five strokes to depict the heads, elongated necks, bodies and legs. Below, the five running dogs have pointed heads, long thin bodies, stretched out legs and curly tails. Finally, the ibexes’ horns take the shape of two concentric circles twice as large as the animals’ bodies. These are reduced to triangles, with a few strokes added to represent ears, beards and bushy tails. In fact, in the preliterate compositions, animal and human figures tend to be transformed into sheer geometric motifs. On the Susa tumbler, (Fig. 4) the long necked birds are stretched into vertical lines, the running dogs into horizontal lines and the ibex horns into circles. In the case of the Tall-I Jari anthropomorphic composition (Fig. 9), the men’s bodies are twisted into a dynamic spiral by minimizing the upper part of the bodies and emphasizing the lower part.

Also typical of the preliterate pottery painting compositions is the static character of the figures and their lack of interaction. The sixty birds perched on the same line on the Susa goblet (Fig. 4) are just standing still, tightly packed together, showing no awareness of one another. The total disregard of the animals for their own kind is only matched by their utter indifference to the other species. The birds are unaware of the dogs and, in turn, the running dogs are oblivious to the ibexes. Vice versa, the ibexes pay no attention to either the dogs or the birds. In fact the painter isolated each species in separate panels. Five lines separate the water birds from the dogs; the dogs run between two sets of double lines, and the ibexes are tightly framed bracketed between bold broken lines. The total indifference of the beasts is exacerbated by their boustrophedon disposition around the tumbler, that is, each species faces in the opposite directions from the one above. The birds are turned to the left, the dogs run towards the right, and the ibex again look towards left. Furthermore, the dogs are not aligned with the ibexes and therefore appear out of step.

The human silhouettes, like the stylized animals, are merely paratactic. (Figs. 6-9) There is no attempt at distinguishing any of the figures by their size, with status symbols such as a headdress or a robe, or executing a different step. Also, like in the animal compositions, no landscape is ever suggested, nor are any on-lookers ever pictured to provide clues about the physical or social context.

The partitioning of panels and friezes between parallel lines is another hallmark of the preliterate geometric, theriomorphic and anthropomorphic compositions. The Samarra vessels (Figs 1 and 2) utilized alternatively 9 and 8 parallel lines, some in sets of two or three. The elaborate composition of the Susa tumbler (Fig. 4) was organized around 13 parallel lines in various thicknesses.

Finally, the painted pottery compositions of the preliterate period shared a remarkable esthetic quality. Pattern repetition conferred harmony; the emphatic linear partitioning gave clarity, and the combination of designs was always striking and original. Perhaps the most significant feature of this discussion was the fact that the compositions did not rely on one design or one frieze alone but on the overall design created by multiple registers of repeated motifs. In other words, a composition such as that of the Susa tumbler (Fig. 4) was to be apprehended at a glance in its entirety, capitalizing on the contrasting vertical, horizontal and circular accents of the geometrized birds, dogs and ibexes. It is likely that the elaborate painted decorations were meant for an exclusively aesthetic function although it is conceivable that some of the designs, such as the triangle and the ibex, might have had a symbolic meaning. If it was so, the repetitive triangles or ibexes could well have brought particular concepts to the mind of the users, in which case, the prehistoric compositions evoked ideas – but they did not tell a story.

Pottery Paintings in the Literate Period

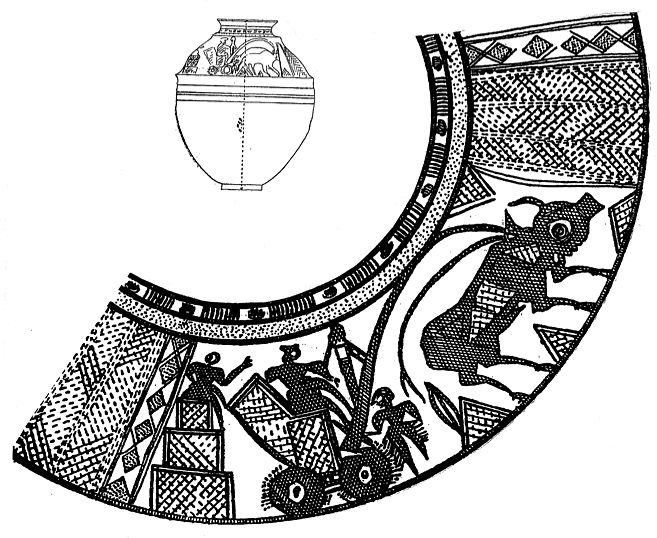

After a break of some 600 years, when Near Eastern potteries were colored in solid red, grey or black and highly polished, design paintings resumed about 2900 BC. Mesopotamian and Persian jars were, once again, decorated with registers of geometric, animal and human figures in a new scarlet hue. Some of these compositions continued the preliterate geometric tradition, but others stood out as fundamentally different. This is the case for a chariot scene painted on a large carinated jar of the Susa II period, ca. 2500 BC.[15] The composition involves three individuals: a charioteer, his attendant and a bystander. (Fig. 12) Below, I compare and contrast this remarkable scene to the previous preliterate compositions

Compared to the lines of identical figures of the preliterate period, each of the personages in the Susa scene is distinctly individualized by garb, context and gesture. The charioteer sports a flat cap probably indicative of his status, the bystander is dressed in a tunic with voluminous sleeves, and the bare-headed attendant wears fringed attire. Each figure is also singled out by a specific context. The hero is seated in his four wheeled vehicle, the on-looker is perched on a three-tiered tower and the attendant is standing, squeezed between the wheels and the draft ox. Finally, each individual has singular gestures. The charioteer is ready to pull the reins for departure, the bystander waves her hand emphatically, and the attendant bustles around the equipage.

Whereas the preliterate pottery paintings strived towards the utmost stylization, those of the literate period are descriptive. For example the draft ox has the big round eyes, curved horns, a long tail and hoofs that immediately identify the species. The picture of the chariot includes many accurate details: the box is made of wicker work; it is provided with a high front pierced with an opening to pass the reins; the draft pole is curved; the solid wheels rotate around an axle and show a copious set of copper nails securing the leather tires.

The function of lines is a third major difference between the preliterate and literate paintings. Whereas the prehistoric lines were used as dividers, those on the late Susa jar unite the individuals in the composition. In the chariot scene, the tower, the wheels of the chariot, the attendant’s feet and the animal hooves are all aligned to form an imaginary ground line. Ground lines are important because they signify that all the connected figures share a same space at the same time as co-participants in a specific event. Therefore, each of the protagonists on the Susa jar was to be interpreted in relation to the other figures. Namely, differences in garb, and size of the figures revealed the identity and relative importance of each individual. The gestures, location/order and the direction of their gaze revealed the role of each protagonist in the scene. I propose that these novel principles guiding the organization of images were learned from writing. In order to make my case, I present below strategies used by the scribes of the late 4th Millennium BC to communicate information and how these strategies were applied to art.

The Strategies of Writing applied to visual Art

In the first centuries of its existence, writing was used exclusively to record entries and expenditures of goods. A tablet featuring an account of grain, (Fig. 13) illustrates how information was conveyed by the form and size of the signs and their location and order on the tablets.[16] I further show how the same paradigm was successfully utilized in the Susa charioteer composition.

Form

- In writing, the form of the signs designated the merchandise dealt with. Wedges and circular signs stood for different specific measures of grain.

- In the painting composition, the form of the figures designated the personalities involved.

- A. Costume indicated sex, age and rank: the charioteer is a noble male; the bystander is a prestigious female; the attendant is a young male.

- B. The gestures denoted action: the charioteer pulls the reins for departure; the female waives good bye; the attendant furbishes the chariot.

Size

- On the tablet, circular signs appear in two sizes: large and small, standing for larger and smaller units of grain.

- In the Susa painting, the large size of the charioteer and the wide space he occupies on the ground line, points to him as the hero of the scene.

Location

- On the tablets, the larger units of goods were placed at the top, followed by lines of lesser and lesser units. (large wedges represent the largest units of grain, followed by circular signs)

- On the Susa vase, the placement of figures on the ground line signals their relative importance in the scene. The most important personage is in the center, the secondary figures are on either side, the figure behind the hero being of least importance.

Order/Direction

- In the Mesopotamian writing system, when different signs were entered on the same line, the larger units were on the right and the lesser ones on the left. (on the second line of the tablet the larger circular sign is placed to the right and those smaller to the left.)

- In the Susa composition the order/direction of the figures conveyed the dynamics of a scene. The bystander and the attendant direct their gaze towards the main actor. The charioteer looks ahead, never turning to acknowledge the farewell gesture, and thus denotes his priorities.

It is logical to assume that once the semantic paradigm of writing had been practiced and internalized it could easily be applied to visual art. As a result, after 3200 BC, viewing a picture became akin to reading a text because in both media, the value of signs/images changed according to their shape/size/position/order and direction. By doing so, art increased its capacity to communicate information, namely, art acquired the ability to tell a story. The Susa II painting can depict the departure of a noble charioteer to some heroic adventure, leaving behind with no regrets loved ones and retinue.

Conclusion

During prehistory, pottery paintings consisted of repeated images forming striking aesthetic designs. Pottery painting compositions changed fundamentally in the literate period by becoming narrative. I propose that the transformation be credited to the paradigm developed by writing to communicate information. Consciously or unconsciously the pottery painters treated the figures of an image according to the principles governing the signs of script. The pottery paintings of the literate period thus emulated writing and by doing so images were able to tell complex stories involving multiple figures, whereas preliterate pottery paintings could only evoke an idea.

End Notes

[1] Denise Schmandt-Besserat, When Writing Met Art, The University of Texas Press, Austin 2007.

[2] Ernst Herzfeld, Die Vorgeschichtlichen Toepfereien von Samarra, Berlin 1930, p. 65, fig. 138, no 164.

[3] Phillis Ackerman, “Symbol and Myth in Prehistoric Ceramic Ornament,” in Arthur Upham Pope, A Survey of Persian Art, XIV, Oxford 1967. P. 2919, Fig. 997.

[4] Pierre Amiet, Elam, Auvers-sur-Oise 1966, p. 41, fig. 13.

[5] J. de Morgan, G. Jequier, J.-E. Gautier, G. Lampre, Memoires de la Delegation en Perse, Vol. VIII, Recherches Archeologiques, 3eme serie, Fouilles de Tepe Moussian, Editions Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1905, p. 121, fig. 214.

[6] Yosef Garfinkel, Dancing at the Dawn of Agriculture, Austin, Texas, 2003, pp. 163-198.

[7] J-E. Gautier and G. Lampre, ‘Fouilles de Moussian,’ in J. de Morgan, G. Je?quier, J-E Gauthier, Recherches arche?ologiques, 3ème Se?rie, Me?moires de la De?le?gation arche?ologique en Perse VIII, eds J. de Morgan, G.Jequier, J.-E. Gauthier, Paris, 1905, fig. 254.

[8] Max Freiherr von Oppenheim, Tell Halaf, Vol. I, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1943, Pl. XV:5.

[9]Max Freiherr von Oppenheim, Tell Halaf, Vol. I, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1943, Pl. LX:2.

[10] Roman Ghirshman, Bichapour II Les Mosaiques Sassanides, Paris 1956 p. 111, fig. 22.

[11] Max Freiherr von Oppenheim, Tell Halaf, Vol. I, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1943, Pl. LX.

[12] Amiet, Elam, Auvers-sur-Oise 1966, p. 44, fig. 16.

[13] I. H. Hijara, The Halaf Period in Northern Mesopotamia, London 1997, p. 79, pl. XLVIIIA; ‘Arpachiyah 1976,’ Iraq, XLII, part 2, 1980, p. 133 and fig 10; ‘Three New Graves at Arpachiyah,’ World Archaeology 10, no. 2, 1978, pp. 125-6, fig. 1. I list here the unusual features concerning the vessel: 1) at Arpachiyah tombs were located within the inhabited area, but Grave 2, that yielded the bowl, was outside the settlement. 2) Burials of the Halaf culture were individual, each tomb holding a skeleton laid in fetal position, but Grave 2 yielded four skulls, each placed in vessels, and no other skeletal remains. 3) The 5 vessels contained in Grave 2 stood out from the remainder of the pottery at the site for their outstanding quality; 4) the usual motifs of Arpachiyah pottery painting are geometric designs such as diamonds, triangles and checkers. The bowl is unique in displaying humans. Perhaps most importantly, 5) Phases 2- 4 at Arpachiyah, the period of the grave, differ significantly from other full fledged Halaf sites, such as Yarim Tepe in that it produced an unusual administrative assemblage of complex tokens, otherwise found exclusively in Proto-literate sites. The multipart painted composition, the unusual burial, the complex tokens, all suggest circumstances that are not yet understood (Denise Schmandt-Besserat, Before Writing, II, A Catalogue of Near Eastern Tokens, Austin 1992, pp.160-2, types 13,14, 15.)

[14] M.W. Green and Hans J. Nissen, Zeichenliste der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk, Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Uruk-Warka, Vol. II, Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 1987.p. 197: 134.

[15] R. de Mecquenem, G. Contenau, R. Pfister and N. Belaiew, Me?moires de la mission arche?ologique en Iran, XXIX, Paris, 1943, pp. 103-4, p. 87 fig. 72:22 and p. 105, fig 79:1.

[16] Denise Schmandt-Besserat, How Writing Came About, The University of Texas Press, Austin 1996, p. 59, fig. 19.

Page Updated 3/28/14