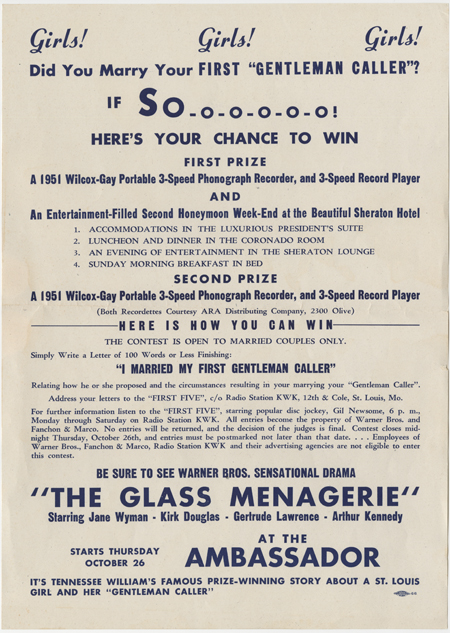

Williams’s copy of the screenplay includes his own note: “A horrible thing! Certified as such by Tennessee Williams.” The film’s manufactured happy ending is reinforced in the flyer for a promotional contest in which “Girls! Girls! Girls!” are invited to send in a letter describing how “I Married My First Gentleman Caller” with the chance to win a second honeymoon at the Sheraton Hotel (breakfast in bed Sunday morning!) and a 1951 Wilcox-Gay Portable 3-Speed phonograph recorder and 3-speed record player.

In a 1950 letter to Jack Warner after seeing the film, Williams outlines his major grievances with the adaptation, centered around his own understanding of Menagerie as a play full of dignity and poetry. Williams calls the inclusion of a flashback scene in which a young Amanda receives numerous gentleman callers and marriage proposals, “a bit of an MGM musical suddenly thrown into the middle of the picture.” He also takes issue with the script changes to Tom’s “drunk scenes,” which are treated in a comic manner that does “untold damage to the dignity of the picture as a whole.”

Williams’s greatest complaint, however, is that the producers have cut lines from Tom’s farewell to his sister Laura, allegedly in response to worries that the lines imply an incestuous relationship between the two. The outraged Williams writes: “I cannot understand acquiescence to this sort of foul-minded and utterly stupid tyranny, especially in the case of a film as totally clean and pure, as remarkably devoid of anything sexual or even sensual, as the ‘Menagerie,’ both as a play and a picture. The charge is insulting to me, to my family, and an effrontery to the entire motion-picture industry!”

The disastrous film adaption of The Glass Menagerie clashes with the play’s positive reception. The Glass Menagerie opened in Chicago for its pre-Broadway run on December 26, 1944. Claudia Cassidy’s positive review in The Chicago Sunday Tribune, dated January 7, 1945, is widely credited with helping make The Glass Menagerie a box-office success in Chicago and ensuring its transfer to Broadway. The least disguised and most autobiographical of Tennessee Williams’s plays, The Glass Menagerie elevated Williams to immediate celebrity where he was applauded as loudly for Menagerie as he was booed for his first play, Battle of Angels (1940). Williams later described this “thrust into sudden prominence” as “the catastrophe of Success.”

Behind this accomplishment was a process that Williams had begun to master, that of transforming individual life experience into art. Place, family, hopes, dreams, and desperation converge in this “memory” play in ways that highlighted the universal qualities of individual experience and that changed the American theater.

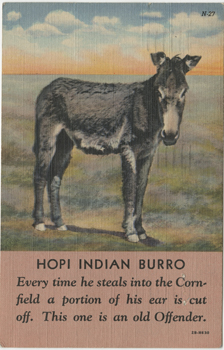

Williams was not new to frustrating Hollywood experiences. While visiting Frieda Lawrence, the widow of the British novelist D. H. Lawrence, in Taos, New Mexico, a year before the great success of The Glass Menagerie, Williams writes to his agent, Audrey Wood, on a post card embossed with the image of an ear-clipped burro, “Picture = me after several adventures with cinema and stage!”

The marketing poster and burro postcard can be seen in the Ransom Center’s exhibition Becoming Tennessee Williams, which runs through July 31.