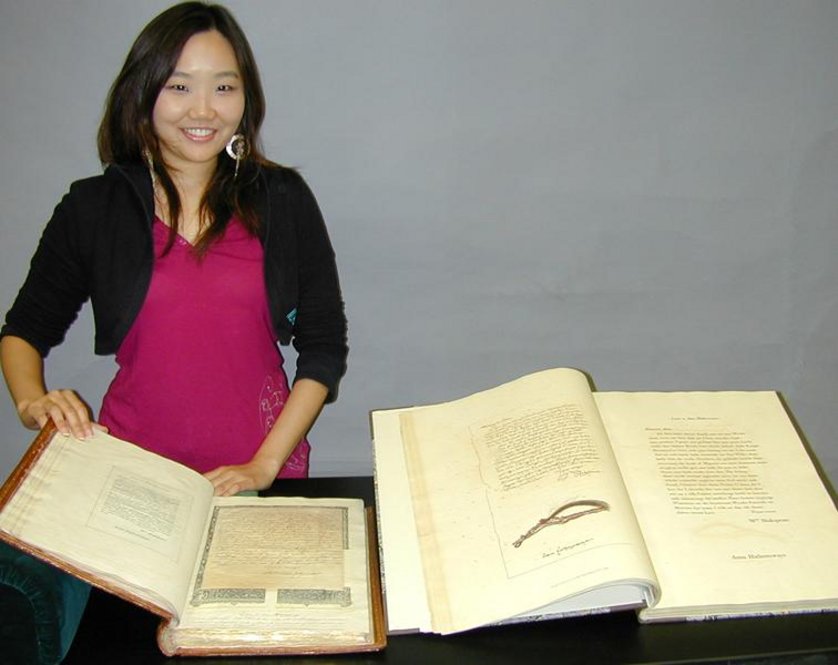

“I’m happy that this book is stable enough for scholars to use,” said Inkyung Youm, a graduate intern in the Ransom Center’s Conservation Department, when asked about the most satisfying part of conserving a book of fabricated Shakespearian manuscripts.

When Miscellaneous Papers and Legal Instruments under the Hand and Seal of William Shakespeare first crossed Inkyung’s workbench, time had taken its toll. The book had split apart in several places. The leather that remained on the binding was chemically deteriorated, and the covers were detached from the text block. Thankfully, the paper was in fairly good condition despite some foxing, a term applied to orangish spots, often present in older paper, that are attributed to deteriorating mold spores or microscopic bits of metal.

Samuel Ireland, an engraver and publisher of travelogues, published this printed collection of alleged Shakespeare manuscripts. Later, the manuscripts that inspired the publication were revealed as forgeries made by his son, William Henry Ireland.

In two published exposés that chronicle his voyage down the slippery path of a forger, William Henry recalls the 1792 trip he took with his father, Samuel, to Shakespeare’s hometown of Stratford-on-Avon. Samuel Ireland, a fervent enthusiast of everything Shakespeare, hoped to discover Shakespearian heirlooms and tracked a promising lead to Clopton House, home of a Mr. Williams. To his father’s horror, Mr. Williams facetiously told Samuel he should have arrived sooner: “Why it isn’t a fortnight since I destroyed several baskets-full of letters and papers, in order to clear a small chamber for some young partridges which I wish to bring up alive: and as to Shakespeare, why there were many bundles with his name wrote upon them.” Missing the joke entirely, Samuel burst out in anger: “Good God, Sir! You do not know what an injury the world has sustained by the loss of them.”

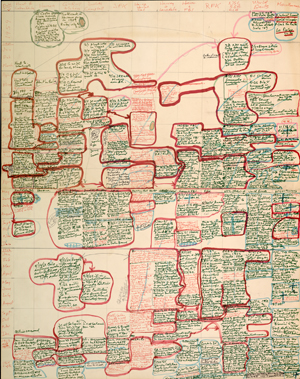

The trip to Stratford-on-Avon and his father’s love of Shakespeare clearly inspired the 17-year-old William Henry Ireland. Two years later, in 1794, young William Henry “procured” from an anonymous gentleman a lease agreement between William Shakespeare and Michael Fraser. He presented this document to his father, who was enormously delighted. The lease was a fake, as were the dozens of other items William Henry “unearthed” during the following months. His father, though, was convinced they were authentic and in 1796 he published Miscellaneous Papers, a compilation of the forged manuscripts.

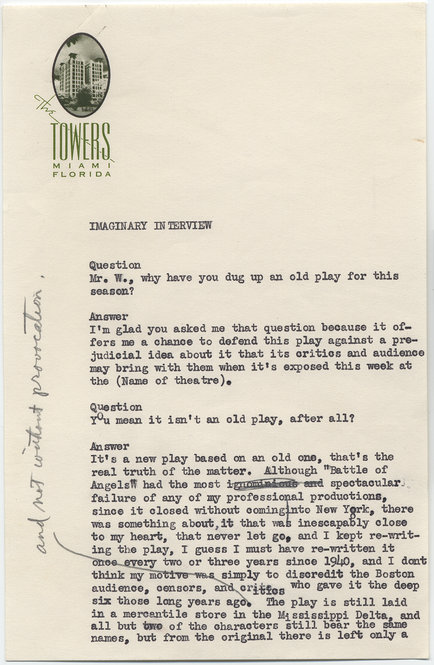

Among the forged manuscripts that William Henry “discovered” was a lost manuscript of a play titled Vortigern & Rowena. At the same time that he published the forged manuscripts, Samuel Ireland negotiated to have the lost tragedy produced at Drury-Lane. The audience was filled with doubters, including antiquarian Edmond Malone, who questioned the play’s authenticity in An Inquiry into the Authenticity of Certain Miscellaneous Papers and Legal Instruments. Even the renowned actor John Philip Kemble, playing the role of Vortigern, doubted the play’s authenticity and decided to give the tragic role a comic turn. The premiere was the play’s only performance.

The critics began to accuse Samuel Ireland of making the forgeries. Hoping to “exculpate my father from the odium which was heaped on him [instead],” William Henry published a pamphlet in late 1796, An Authentic Account of the Shaksperian Manuscripts, confessing that he forged the manuscripts. Nevertheless, it seems that Samuel Ireland thought his son a dullard and refused to believe that he had the skills to compose and write the forgeries—Samuel went to his death in 1800 still believing in the manuscripts’ veracity.

In the preface to his 1805 book, The Confessions of William Henry Ireland, William Henry wrote that he preferred that his actions be “regarded rather as that of an unthinking and impetuous boy than of a sordid and avaricious fabricator instigated by the mean desire of securing pecuniary emolument.” He describes in detail his forging methods and reiterates that he wanted to please his father with these gifts. He admits that pride in his own forging abilities led him to undertake some of the projects.

William Henry made a business of his scandal until his death in 1835. He cashed in by selling sets of “original” forgeries to collectors. One such copy of the handwritten forgeries, which originally was presented to the Prince Regent (later George IV), was acquired by the Center in the 1980s.

Conservators often study the historical background as well as technical information relating to an artifact to enhance their understanding of the artifact and to guide their treatment methodology. “At the Ransom Center, our approach to conservation treatment is usually quite conservative to safeguard physical information intrinsic to the item. Usually, we stabilize the physical structure and, sometimes, the chemical condition of a book so that patrons can safely handle the item,” says Ransom Center Book Conservator Olivia Primanis.

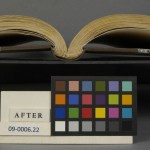

Originally, Inkyung planned a conservative treatment: to repair the book structure by reattaching the covers to the book with tackets, a technique that reconnects covers to the text block by looping thread through small holes that are pierced in the cover and through the shoulder of a text block. This repair would have left the book close to its original state, but the binding structure proved to be too deteriorated for a minor repair. While Inkyung was working on the book, the sewing threads broke, which required that the book be disassembled. Once apart, Inkyung mended tears in the pages and guarded the single leaves into gatherings with long-fibered Japanese paper and then resewed the book.

“This is a big job,” says Primanis, “especially when the book is large in size. This one measures 44 centimeters by 33.7 centimeters.”

Inkyung made a new cover for the book since the marbled paper covering and much of the original leather that remained were chemically deteriorated. Inkyung made the new cover with a marbled paper that had a pattern similar to the original cover and book cloth, which, today, is considered more durable than most newly made leathers.

Inkyung constructed a housing for the book that accommodates the original cover. Because deteriorated leather can stain adjacent materials, a folder was made for the original cover to protect the new binding.

Evidence of William Henry Ireland’s hoax lives on in the manuscript facsimiles and the printed publication. Because the book is working as a book should, Ransom Center patrons can now safely handle and study the forged Shakespearian manuscripts along with other texts revealing the context of these fabrications. These volumes might also be called on by those interested in background information on the recently published monograph inspired by the life of William Henry Ireland, The Tragedy of Arthur by Arthur Phillips.

Please click the thumbnails to view full-size images.