The Harry Ransom Center is proud to announce that our collection of materials relating to the 1866 megamusical The Black Crook has been fully digitized in celebration of the 150th anniversary of the production. The collection is now publicly available through our online Digital Collections gallery.

![Napoleon Sarony (American, 1821-1879), [Pauline Markham in a production of The Black Crook], undated, Albumen print, 10.0 x 14.2 cm, The Black Crook Collection.](https://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/files/2016/09/PA_Black_Crook_1_39_005.jpg)

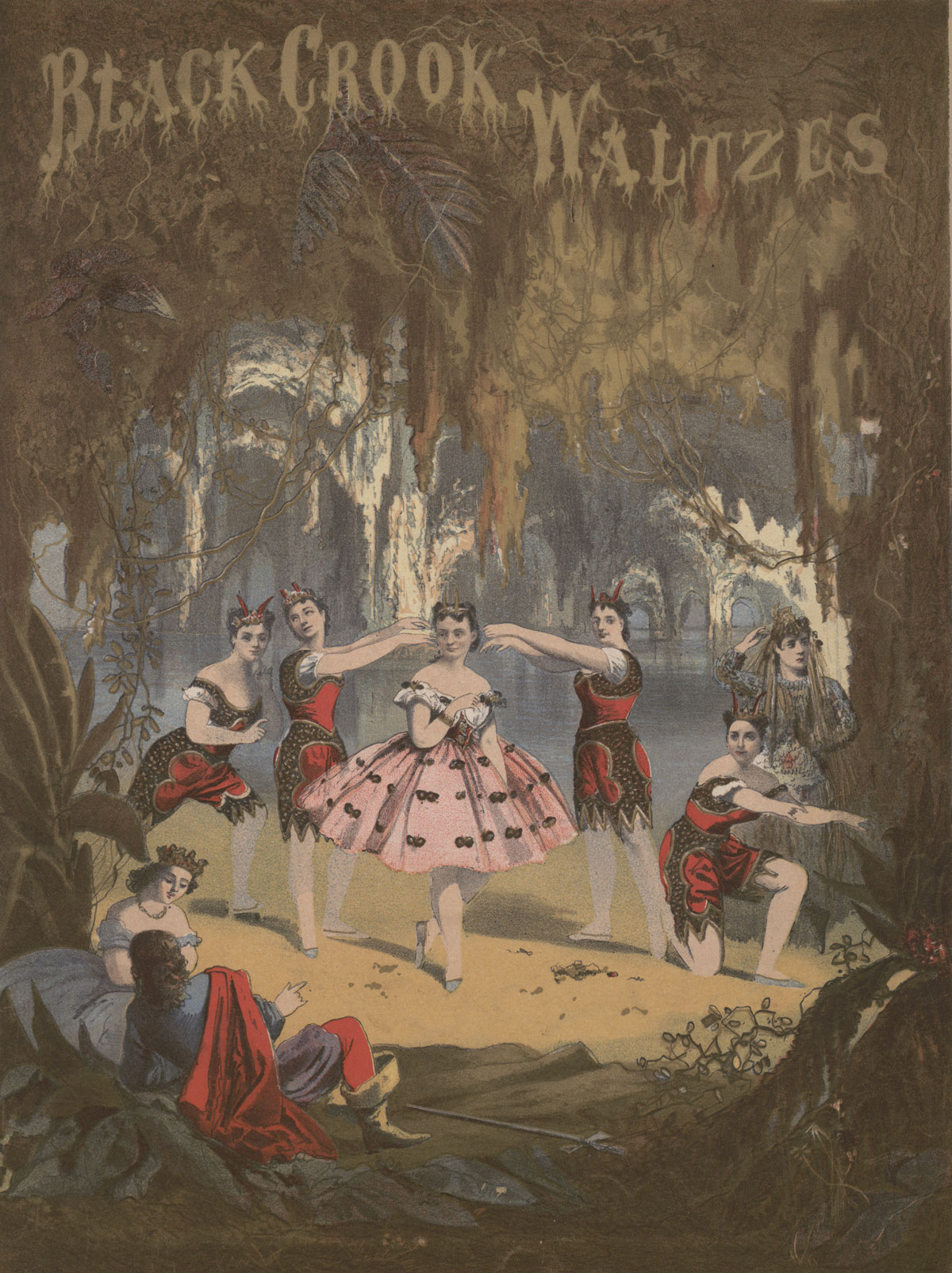

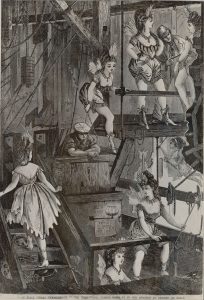

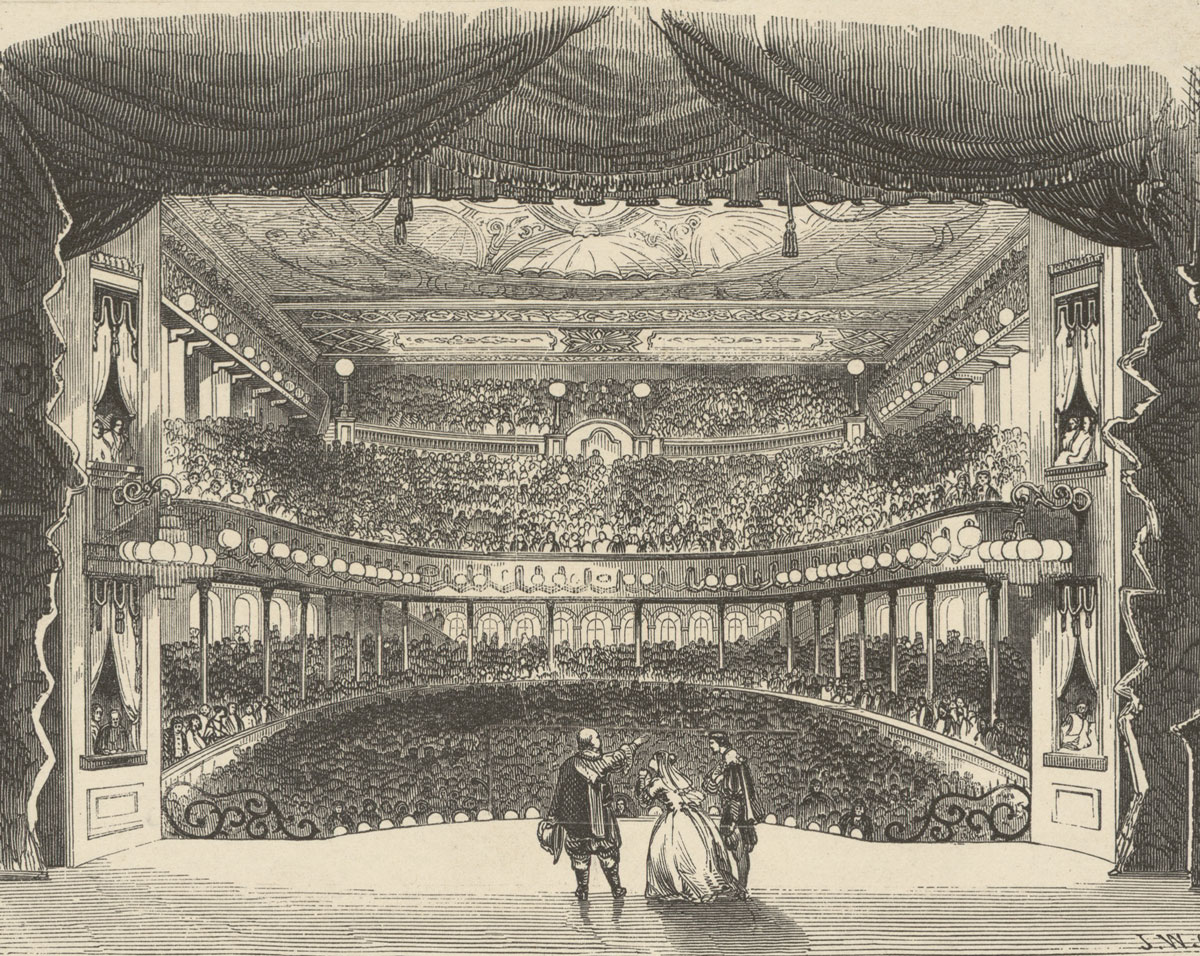

The opening night performance ran over six hours and offered a full evening’s entertainment of comedy, drama, romance, tragedy, dance, music, and unparalleled spectacle. The scenic machinery had been imported from Europe and cost between $25,000 and $55,000—an enormous sum for the time. It is rumored to have taken over 50 stagehands to operate. A chorus of over 100 dancers performed as fairies in the glittering cave of Queen Stalacta in one scene, and in another, advanced lighting effects created a hurricane in the Harz mountains of Northern Germany.

Many of the dancers wore flesh-colored tights, making it appear that their legs were scandalously nude, much to the delight of audiences and chagrin of critics. Preachers denounced the show from their pulpits, and artists lamented the direction the American theater seemed to be heading.

In a letter from the Ransom Center collections, the acclaimed American actor Edwin Forrest wrote to his solicitor and friend Daniel Dougherty about the state of the American theater. “The Black Crook—alas for the public taste—is quite as successful as when it was first performed more than a year ago.” Charles Dickens was even more pointed in a March 1968 letter to the English actor William Charles Macready:

I will mention here that one of the Proprietors of my New York Hotel is one of the Proprietors of Niblo’s and the most active. Consequently, I have seen The Black Crook and The White Faun in majesty from an arm-chair in the first entrance. P.S. more than once. Of these astonishing dramas, I beg to report (seriously) that I have found no human creature “behind,” who has the slightest idea what they are about (‘pon my honor, my Dearest Macready!) and that having some amiable small talk with a neat little Spanish woman who is the Première Danseuse, I asked her, in joke, to let me measure her skirt with my dress glove. Holding the glove by the tip of the fore-finger, I found the skirt to be just three gloves long—and yet its length was much in excess of the skirts of 200 other ladies whom the carpenters were, at that moment, getting into their places for a transformation scene—on revolving columns—on wire and travellers—in iron cradles—up in the flies down in the cellars—on every possible description of float that Wilmot, gone distracted, could imagine.

(From The Selected Letters of Charles Dickens. Edited by F. W. Dupee. New York: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, 1960)

Dickens made it clear, as did many newspaper reviewers, that the enormous popularity of the production was owed not to the book by Charles Barras or the music by Thomas Baker, but rather by the spectacle and sexuality offered to audiences.

The Black Crook would be revived for decades until about the 1940s when the advent of World War II and the changing tastes of the American theater made it fall out of favor. As part of the 150th anniversary celebrations, a small-scale revival will be remounted at the Abrons Art Center in New York from September 17 through October 6, 2016.

The collection of Black Crook materials at the Ransom Center includes original sheet music, playbills, programs, clippings, drawings, photographs, and books relating to the first production and its subsequent iterations. These materials can now be viewed online through the Ransom Center’s Digital Collections gallery.

Dr. Eric Colleary is the Cline Curator of Theater and Performing Arts at the Harry Ransom Center.