Eric White, Curator of Rare Books at Princeton University, discusses the Ransom Center’s Gutenberg Bible on Thursday, February 9, at 7 p.m. for the Center’s annual Pforzheimer lecture.

White’s talk, “From Mainz to Austin: Carl H. Pforzheimer’s Gutenberg Bible and its Earlier Owners,” will focus on recent scholarship and new discoveries related to the book’s early provenance. A reception follows the event. The Center’s Gutenberg Bible is on permanent display.

In advance of his visit, White shares his insights about the Gutenberg Bible, variations that exist among copies of the Bible, and what distinguishes the Ransom Center’s copy.

As a curator of rare books, what does the Gutenberg Bible represent in your field?

The Gutenberg Bible represents, for historians of European printing, both the book about which we know the most and for which we still have the most questions. It stands at the beginning of the typographic tradition, and therefore presents many questions about the origins of printing with moveable types in the West. Scholars have been arguing about it for about 300 years, so you know it’s a good topic.

In this new age of technology and e-books, do you think there is a renewed interest in early printed books including the Gutenberg Bible? Are there parallels between the revolution created by the Bible’s printing and that created by the development of electronic books?

I think there is a fascinating relationship between the rise of European printing in the fifteenth century and the arrival of the digital information age. The pioneers in Mainz circa 1450 had to figure out how to make books, which books to make, and how to market them, while facing severe technical challenges and economic risks. They faced the questions of quality versus quantity, speed versus accuracy, and tradition versus innovation. Almost immediately there were serious financial flops, questions of censorship, and cut-throat competition. But most people adjusted to the new books and liked them, and more people had access to reading information than ever before. If students of today’s society do not find these precedents useful or interesting, perhaps they should look again.

What do you find most intriguing about the Ransom Center’s Gutenberg Bible?

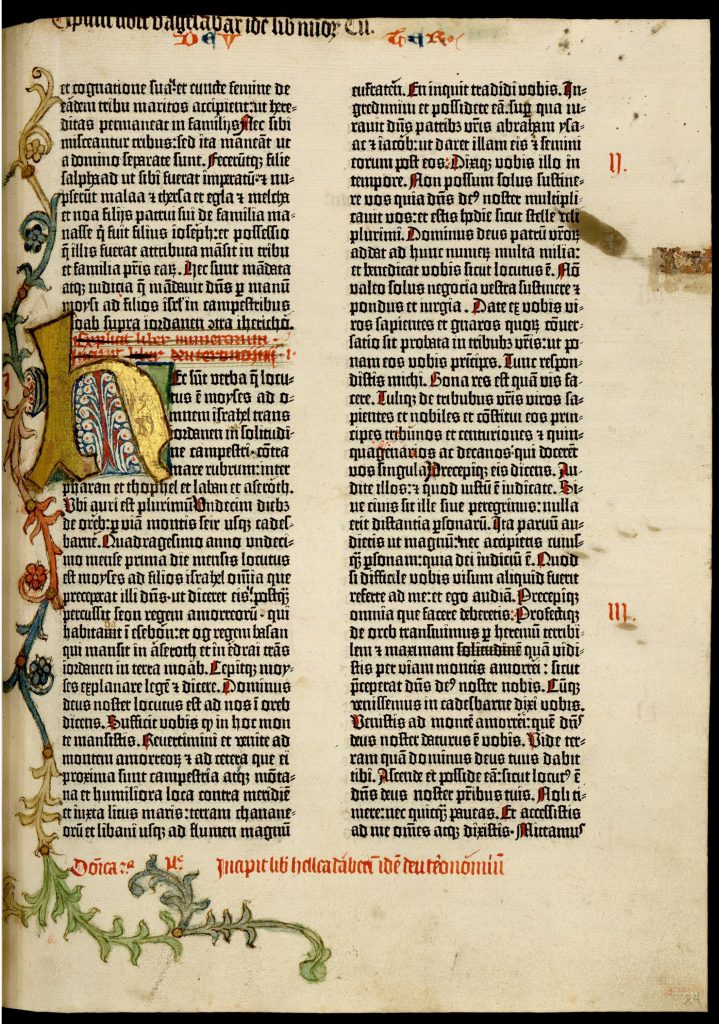

The Texas copy of the Gutenberg Bible, more than any other, has undergone a drastic change in responses to it. When it was found exactly 200 years ago, it was introduced to the market as a “fine copy,” but no one really believed that; by 1863 a learned Bishop called it a “poor one.” Throughout most of the twentieth century, no one appreciated all the scribbling of notes and liturgical reading markers added by forgotten monks, while the decoration appeared to be less fancy than others, and kind of weird. Since the Bible came to Texas in 1978, scholars have been drawn to it as perhaps the most interesting of all the copies, because its annotations give us so much information about its original context and usage, and the weird decoration presents an ongoing mystery. I’ve been working on this for about a dozen years, and I think I’m finally getting close to the answer, or at least a new set of questions.

What has been one of the most rewarding experiences in your career as a curator of rare books?

One of the most rewarding things about curating rare books has been the opportunity to visit great books in great collections, and to work with the some of the most important evidence of human history first hand. I’ve SEEN dozens of Gutenberg Bibles, but I’ve been able to turn the pages of ten of them for the purpose of learning something new and unexpected—which I did every time.

What initially attracted you to the study and curation of rare books?

I was an art historian, finishing my Ph.D., when I noticed that in many cases it was the museum curators who knew more about the paintings than the university researchers. So when I saw the opportunity to work closely with original things, in a great collection—Southern Methodist University’s Bridwell Library—I really went for it, and I’m glad I did. The transition from paintings to books was easy, utilizing much of the same academic training, but I like old books because they tend to offer many more little un-trodden questions that tend to be more answerable in the long run. Also, I like working with sets of things: eight copies of this book and 20 copies of that book, or five books by this printer or 50 books from that medieval library—not just individual items in isolation. We can work with books like detectives, approaching them from many angles, and we always seem to end up learning new things about the people who used them.

People may not realize there are variations among Gutenberg Bibles. What is unique about the Ransom Center’s copy?

Unless you’re particularly concerned with the exact sequence of Latin words that comprised the medieval scriptures, everything ELSE about the Gutenberg Bibles is unique to each one. Occasional corrections and re-printings, the hand-decoration, the bindings, the signs of use and ownership are all traces of human intervention and history that are particular to that copy. The Texas copy has a unique printing mistake in it, but I think its individual “character” comes from its mismatched bindings, the rich layers of early annotations and markings, and the truly puzzling illuminations of the initials by at least three different artisans.