Eric White, Curator of Rare Books at Princeton University, discusses the Ransom Center’s Gutenberg Bible on Thursday, February 9, at 7 p.m. for the Center’s annual Pforzheimer lecture.

rare books

Recent publications

Alison K. Frazier, Editor

Alison K. Frazier, Editor

The Saint between Manuscript and Print in Italy, 1400–1600

University of Toronto Centre for Renaissance and Reformation Studies, July 2015

The 12 essays in this volume identify mutually interactive developments in media and saints’ cults at a time and in a place when both underwent profound change. Focusing on the Italian peninsula between 1400 and 1600, authors analyze specific sites of intense cultural production and innovation. The volume invites further study of saints of all sorts—canonized, popularly recognized, or self-proclaimed—in the fluid media environment of early modernity. [Read more…] about Recent publications

Archivist traces manuscript waste in a set of volumes back to a dark origin in Frankfurt

It was a bitterly cold day in Frankfurt when my wife and I stepped off the plane. Being from Texas, we quickly found that our bodies were not acclimated to the bitter winter winds of Europe. Our cab dropped us off near the central square of the city so we could get some hot spiced wine at the market. On our way back to our apartment, we spotted a public building across the street, the Museum Judengasse, and decided to take a tour and thaw out before braving the rest of the journey. The museum contained the archeological remains of the Frankfurter Judengasse—the Jewish Ghetto of Frankfurt—one of the earliest ghettos in Germany.

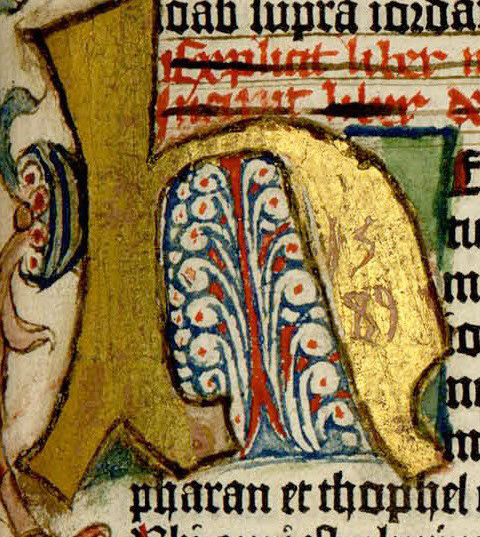

About two years later, I encountered something in the stacks of the Harry Ransom Center that brought me back to that cold day. While conducting a search for medieval manuscript fragments used in bindings of early printed books, I came upon a set of four small volumes of German poetry printed in Frankfurt in 1612 and bound in parchment. The parchment contained medieval Hebrew script. I had not yet encountered this phenomenon (I was used to finding texts in Latin), and, although I posted images of the volumes on Flickr, I received no immediate comments. Several months went by and I had almost forgotten about them when one day I happened to mention the fragments to a colleague who suggested that I contact a Hebrew specialist cataloger. I was then put in touch with the proper authorities and within a few days the fragments had been identified. Included are a fragment from a series of commentaries on late antique Hebrew liturgical poetry (dating anywhere from the twelfth to fifteenth century), a page from the table of contents from a circa fifteenth-century copy of a work by Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil, and fragment from a twelfth–to-fourteenth-century commentary on the Talmud. Having them identified was an exciting example of international collaboration between scholars, but it is the historical context of the fragments that brings this story full circle.

In the sixteenth century, the Jewish community of Frankfurt was one of the most important centers for Rabbinic teaching and spiritual thought. It was also one of the largest Jewish communities in early modern Europe. In 1612 tensions between the town guilds and the patrician class over urban and fiscal policies led to a riot known as the Fettmilch Rising. During the course of the riot the Judengasse, or Jewish Ghetto, was attacked and looted and the Jewish inhabitants were expelled from the city. The volumes at the Ransom Center were printed in the same year as the Fettmilch Rising (1612). Given the looting that took place it is highly probable that the fragments used to cover the printed volumes were sourced from Hebrew manuscripts that had been taken during the riot and then cut up and sold for a variety of purposes—including bookbinding. And so here the volumes now sit, deep in the heart of Texas, a tragic reminder of early modern anti-Semitism in Germany. As an American, it’s often difficult to place these priceless objects in context, and when one does, it tends to have a dramatic effect on the psyche.

Our set happens to be missing two volumes. One can only hope that the other two volumes are still out there intact. This situation underscores why it is important to avoid removing medieval fragments from their bindings. When we do so, the historical context of their use as binder’s waste may be lost. With the power of crowdsourcing and online collaboration, all of the fragments from the original manuscript may someday be reunited in a virtual environment—a happy conclusion to the tragic circumstances of its dispersal many centuries ago.

The post author would like to thank Kevin Auer, Uri Kolodney, Elizabeth Hollender, Ezra Chwat, and Pinchas Roth for their assistance in identifying the Hebrew fragments.