Meet the Staff is a Q&A series on Cultural Compass that highlights the work, experience, and lives of staff at the Harry Ransom Center.

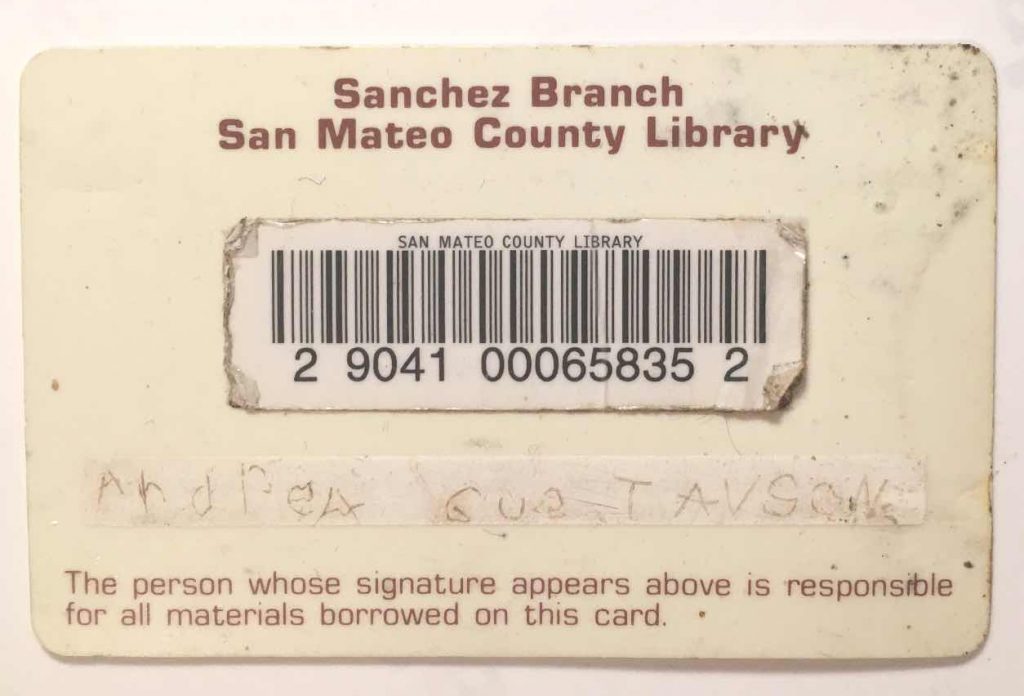

An alumnus of The University of Texas’s American Studies doctoral program, Andi Gustavson first came to the Harry Ransom Center as a graduate intern.

Now she is the Ransom Center’s Instructional Services Coordinator and assists faculty and facilitates students’ use of collection materials in undergraduate classes. Originally from the San Francisco Bay area, Gustavson taught in New Orleans with Teach for America before coming to The University of Texas at Austin and acquiring her Ph.D.

Where did you receive your undergraduate degree from, and what in?

I did my undergraduate work at The University of California, Los Angeles, and I was an English major with a focus on American literature. I really enjoyed it. I graduated early and worked a couple of jobs in order to save up money to backpack for a year. So I spent a year backpacking around before moving to New Orleans to teach high school.

Tell me more about your travels!

I went to Western Europe, Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, spent a little time in North Africa, some time in Turkey, and about three months in India. The trip was just short of a year. I was traveling by myself, but friends would come and meet me here and there. I was very fortunate to be able to do it. India is the place that I remember the most. It definitely made the biggest impression on me.

What attracted you to UT’s American Studies program?

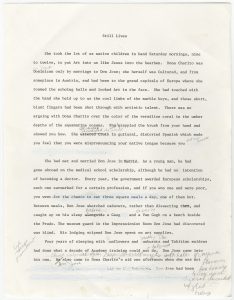

I wrote my undergraduate honors thesis on James Agee and Walker Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and then found out that the Ransom Center has the Agee papers. Originally, I thought I wanted to continue to work on that project, so one of the reasons I came to the Ransom Center, and therefore to UT, was because of that collection. I had also done a lot of research into the faculty, and I knew that I wanted to work with Julia Mickenberg and Steven Hoelscher. When I visited Austin as a prospective student, I also met with Angie Maxwell, who was a graduate student at the time. She is a wonderful person and her scholarship is incredibly dynamic—her enthusiasm about the program made me want to attend. One of the things that attracted me to the American Studies program at UT was the opportunity to develop and teach your own class as a graduate student. I knew that education, specifically higher education, was important to me, and that I wanted to have that opportunity to teach my own class. Fortunately, I was able to develop a class on photography and American culture and taught it here at the Center.

Can you tell me about some of your research?

My own research focuses on snapshot photography, mostly taken by service members or their family members—so mothers, wives, girlfriends. I look at the ways that service members actively frame their own experience of war through the act of taking a photograph. One of my research practices is not unlike what you and I are doing now; I conduct a lot of oral histories with veterans or people affiliated with the military and ask them about their snapshots. I’m hopeful that my work enters into a conversation about who shapes the visual record of war. I argue that these snapshots allow us to see the daily ways in which war takes place and to consider how Americans become accustomed to a culture of ongoing and seemingly unending war.

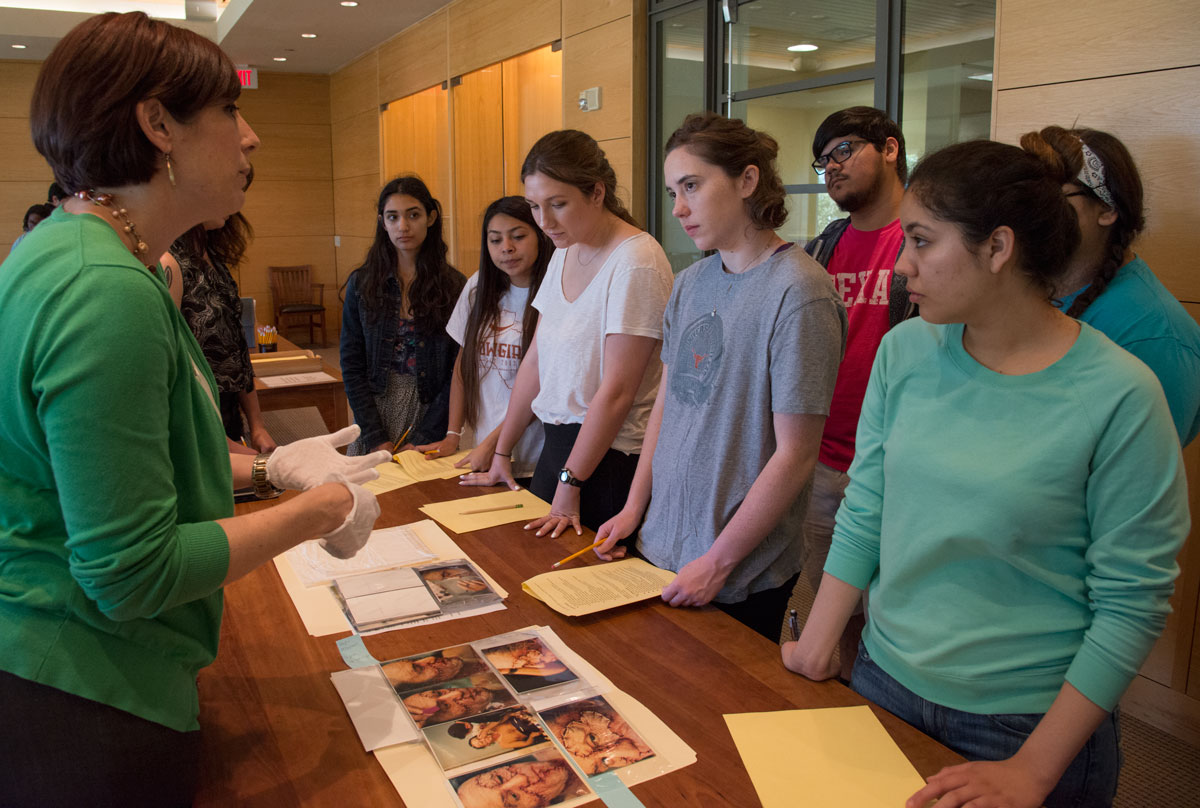

Can you tell me about your job at the Ransom Center?

As the Instructional Services Coordinator, I help faculty and graduate student educators who want to teach with collection material. Often I collaborate with faculty members when they’re designing their syllabus or developing an assignment that makes use of the reading and viewing rooms. We can design a classroom session for a single visit, a multi-visit experience, or even a semester-long course. I’ll meet with faculty to discuss their goals for their students and the central questions guiding their course. Together, we’ll create a lesson that helps them meet those goals while allowing the students to work with the special collections material. It’s an incredibly fun job.

Has your role evolved since you started this position in 2015?

Because my position is a new one for the Ransom Center, I’m learning more each semester about faculty needs and so my role is constantly developing as we take on new and different teaching opportunities. One of the things that’s so exciting about this job is the opportunity to collaborate not only with the faculty and graduate student educators, but with my coworkers within the Ransom Center. My colleagues in description and access, public services, and on the curatorial team will often suggest collection items that they think will teach well. And, of course, teaching is an ever-shifting process. I’ll try something out in the classroom—maybe a new way of engaging the students, a new way of providing access to the material, or a new questioning practice—and I’ll see what works and what falls flat and then re-design the class the next time.

Do you have a favorite collection?

I enjoy teaching with the Julia Alvarez papers. We have a couple of classes that have read How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents and have looked at her manuscript drafts and correspondence with students from her writing programs. Alvarez does quite a bit of research for each of her works and that material remains in her collection so we can draw from the historical and cultural context that informed her writing. And because she went through so many revisions of each manuscript, the students can grapple with the changes she made with each draft. Moreover, because they’ve all read Garcia Girls, the students often know more about the nuances of the text than I do. They’re able to see things in the changes between drafts that I can’t always see.

Have you read any good books lately?

Gold Fame Citrus by Claire Vaye Watkins, and I just started the Elena Ferrante Neapolitan Quartet. I’m halfway through the four works and I’m so engrossed that I’m almost reading too quickly.

If your own photographs were to be archived as a collection, what things do you think people might find interesting? What would your collection say about you?

I think if people were to look through my snapshots they would find the same photographs that are in a lot of people’s collections. Some of that repetitiveness—the mundane quality of snapshot photography—is what I wrote about in my dissertation. We photograph moments that feel significant or ceremonial, so there are lots of photographs of my graduation, my stepson’s birthday, my backpacking trip. I’m also a total ham—so there’s probably a ton of photographs of me putting on plays in grade school and making faces for the camera.

Related content

Teaching with collections in a large-format undergraduate class