A costume worn for the Ballets Russes’s production of Narcisse, currently on display in the exhibition Stories to Tell: Selections from the Harry Ransom Center, presents an intriguing glimpse into behind-the-scenes work at the dance company that electrified pre-World War I audiences in Europe and beyond.

A peek inside the brightly colored, hand-painted dress opens a world beyond the handful of initial performances. The handwritten names of several dancers, a customs stamp, delicate darning stitches, interior construction, and sweat stains reveal the costume’s movement across national boundaries and years of wear and repair by different dancers and unnamed seamstresses, from the original production of Narcisse in 1911 to its revival in the 1920s. Eric Colleary, the Ransom Center’s Cline Curator of Theatre and Performing Arts, and I conferred on the best way to afford visitors a view of this history.

Carefully placed mirrors or cameras around a three-dimensional mannequin, or the flat display of a garment with opened front or back closures can expose the interior of a costume for exhibition. The strategy for display depends upon the fragility and condition of the garment. Although the 116-year-old costume is indeed fragile, the weight of its feather-like muslin fabric alleviated our concerns about inadequate support due to an open back. If made from a weighty fabric such as velvet or embellished with heavy beads or other trim, open display of the costume on a three-dimensional form might not be possible.

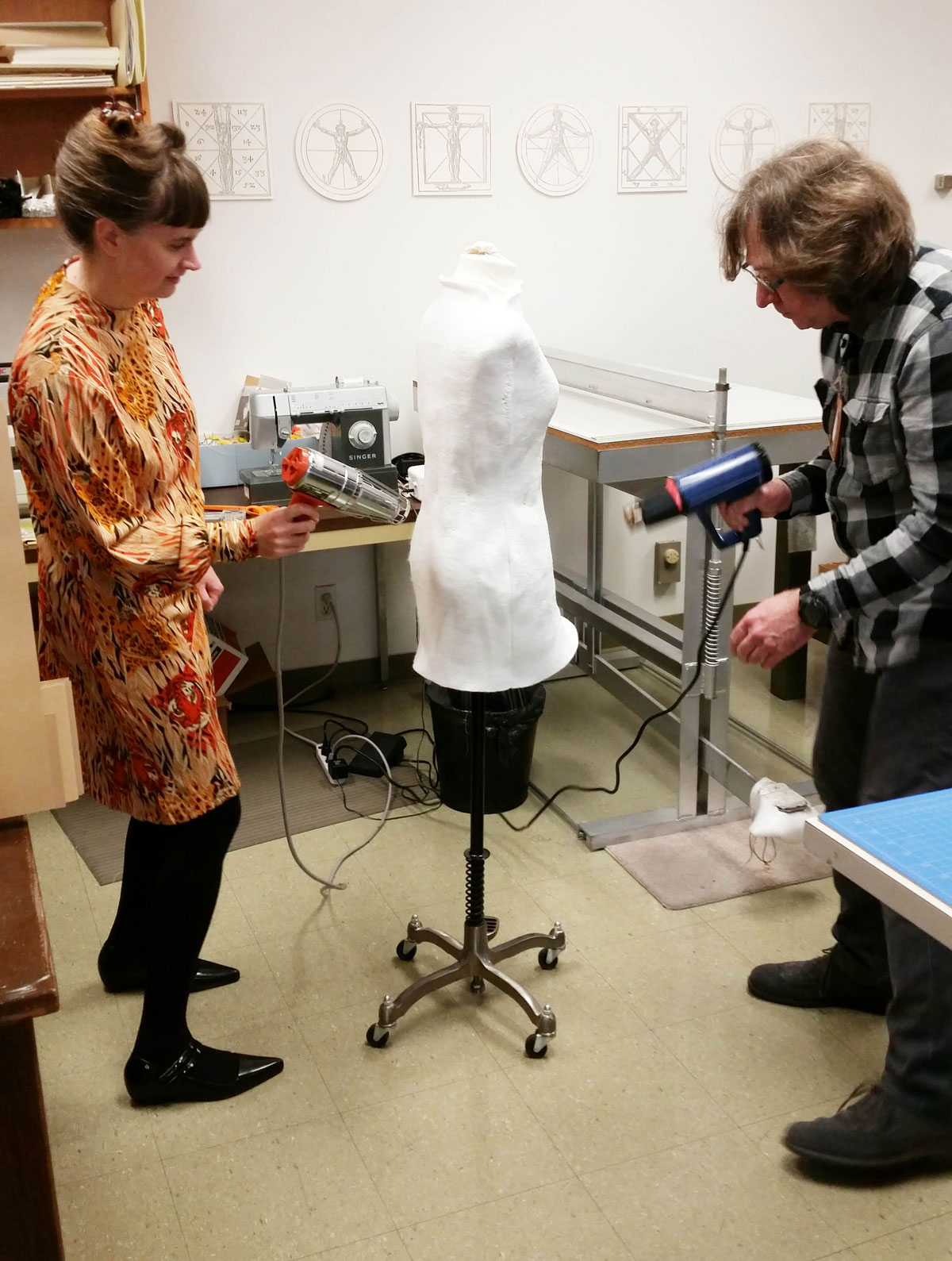

As with a World War I uniform displayed at the Ransom Center several years ago, we returned to Fosshape, a lightweight material that can be easily molded and sewn to make a mannequin. The initial shape is created with heat, which shrinks to the contours of a dress form of correct size and proportion for the costume. The form is then carefully pinned to mark the areas where the Fosshape would be cut away to become an invisible—“floating”—form and reveal the names and additional written information on the inside of the bodice. Once cut away and shaped, we covered the bright white Fosshape with a neutral, flesh-colored fabric.

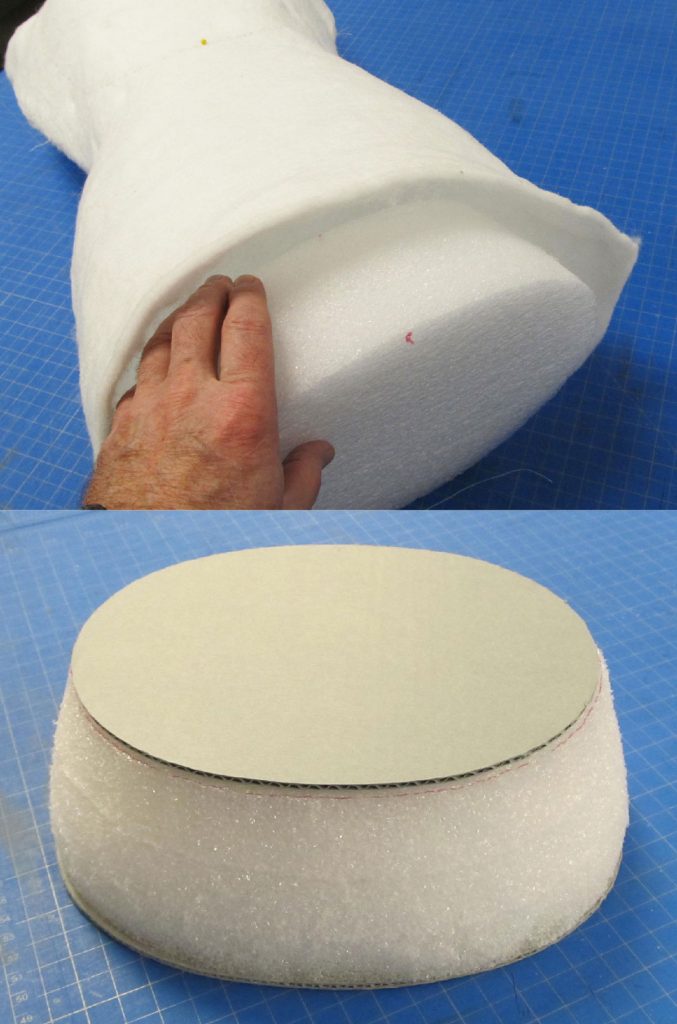

Interior supports made of Rigilene, a material often used in corset making, and precision-cut Ethafoam help provide structure and rigidity to the form. The Ethafoam supports create a flexible structure in which to fit a custom-made acrylic pole and stand, which enhances the feeling of invisibility and weightlessness of the “floating” form.

Even a form with close measurements to the actual costume needs additional support and definition. Polyester batting is used to pad out the chest, hips, and rear, which approximates a softer, more realistic human form. Small hip panniers made from netting and pleated muslin allow the skirt of the costume to drape more naturally.

Finally, two pieces of metal boning—also a material used in corset making—were measured and sewn to the form to help create the illusion of an extended leg and a sense of movement. The most resilient metal hooks and eyes were sewn to the Fosshape form using a thin, clear monofilament thread, to keep the costume supported and connected to the form. Remote-controlled LED lights embedded inside the exhibition case prevent fading of the costume’s colors or degradation of textile fibers.

As noted previously, mannequin-making is rarely a solitary activity. Careful handling of the garment and final design and construction decisions cannot be accomplished alone. This was a joint effort with Exhibition Preparator Wyndell Faulk, with the assistance of Preservation Technician Apryl Sullivan.