This essay is part of a slow research series, What is Research?

Part of what is so compelling about doing research with old books is that the learning curve never ends—there’s always some new challenge, another thing to explain, something else to get to the bottom of.

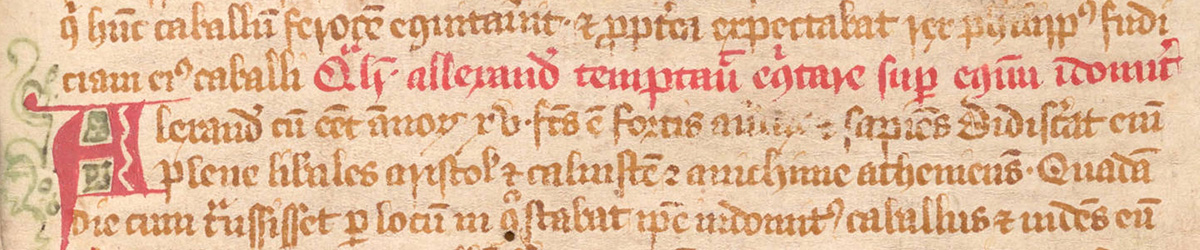

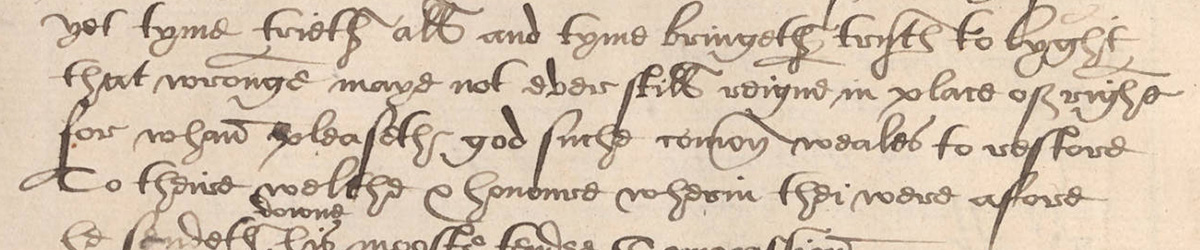

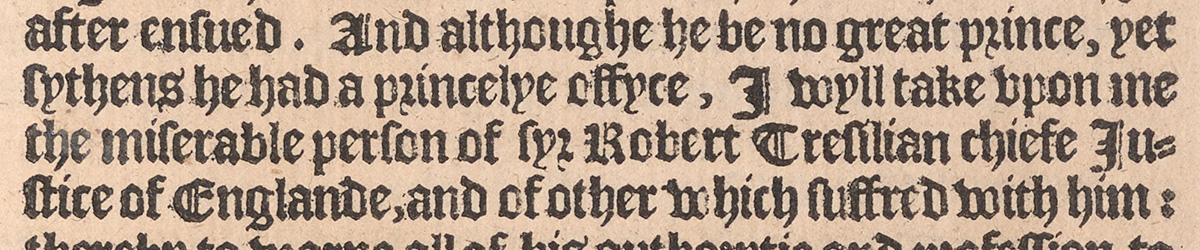

Reading old books is hard. Even if a book isn’t that old, content regularly poses challenges: who is that historical figure, what on earth is this political debate about, is this supposed to be a joke? And if the book is from more than a century or so ago, determining the meaning of basic nouns, verbs, and idioms can be tough, too. If you’re reading a manuscript or early printed edition in a place like the Ransom Center or working with a digital facsimile of one from your couch, you’re also likely to face different typographical conventions, alien styles of handwriting, and unfamiliar abbreviations.

The images below are from three English books in the Center’s medieval and early modern collections, but while they are all from roughly the same place and two are from the same decade, each requires its own set of literacies. And these literacies, of course, take time to develop.

For card-carrying historians and those in other disciplines who approach the study of culture historically, analyzing old books requires yet another skill on top of those needed for comprehension, one that’s perhaps more subtle but is arguably just as important: learning how to read like earlier readers did. It’s one thing to decipher a particularly difficult bit of handwriting and—after much wailing and gnashing of teeth—to comprehend the theological background of a complex satirical poem, but it’s another thing to reconstruct how different types of readers from the past would likely have interpreted the same passage or work themselves.

Any researcher who thinks they can table all of their modern assumptions and be fully objective is fooling themselves. Nevertheless, these efforts in reconstruction are necessary if we want to understand the complex array of motivations, actions, and responses that created the world and defined the horizons of possibility for those who came before us.

—AARON T. PRATT

When I encounter the illustrations in the Center’s manuscript of the Täˀammərä Maryam (Miracles of Mary), for example, I am struck by many things about them; but as someone without expertise in early modern Ethiopian culture, I also know that any off-the-cuff analysis I could offer would be shaped in large part by my viewpoint as a white 21st-century American who researches Europe. It would be obvious pretty quickly that I lack the contextual knowledge needed to accurately approximate what Ethiopian Christians living in the 17th century would have seen in them. In many cases, though, it’s far less easy to catch ourselves when we’re interpreting a historical source or group of historical sources ahistorically. Even seasoned scholars can benefit from the reminder that knowing a lot about historical ingredients does not on its own guarantee that you’ll be able to make a historical recipe.

Efforts to reconstruct the interpretive lenses through which readers in the past themselves saw the books preserved today in special collections libraries are necessarily imperfect and partial: as now, most readers didn’t write down their interpretations and those who did could very well have been idiosyncratic in their approaches, making it difficult to generalize from the evidence of reading that does survive. And any researcher who thinks they can table all of their modern assumptions and be fully objective is fooling themselves. Nevertheless, these efforts in reconstruction are necessary if we want to understand the complex array of motivations, actions, and responses that created the world and defined the horizons of possibility for those who came before us.

Perhaps frustratingly, the work required for historically minded research can be slow-going, because you can’t immerse yourself only in the content you find most fascinating. You may need to sit down and peruse a group of bestselling sermons you’ve never heard of, learn enough Dutch to get into the political discourses that shaped both sides of a cross-cultural exchange, look at maps and globes that testify to new trade routes and emerging imperialism, or spend time with the kinds of archival documents that have the potential to reveal more diverse local populations and more racialized thinking than many now assume there were.

You might also benefit from thinking about books as complex artifacts that extend beyond text and image in an effort to embed yourself in a media ecosystem that differs from ours today. How were books made? How did people buy, sell, and otherwise interact with them, and what might these things tell us about how they approached the content you’re interested in? You may need, too, to understand a range of historical experiences that are best attested to by artifacts—tools, clothing, furniture, entire buildings—that have only left the faintest of impressions in the written record.

Having the discipline to delay judgment and keep honing the lenses through which you read is hard, and it can be hard, too, to know when you can stop researching and start making claims. But this kind of discipline is what it takes to represent the agents of history ethically. I tend to think of it as a discipline of empathy, one that balances a commitment to telling the stories of the past with an eye toward justice in the future against a commitment to representing that past honestly by helping its voices speak as they would have. Even if those voices are troubling, not entirely representative of a population, or just not as interesting as we’d like, they’re nonetheless the voices of individuals and populations that lived, and we have an obligation to try to represent them faithfully.

When you read an old book, you are being asked to enter a different world that only becomes maximally legible when you do the work to engage with it on historically situated terms. Yes, critique is well within the remit of those of us interested in history, but responsible work proceeds first from understanding. And a desire to understand is what brings us to the study of the past in the first place, right?