by COYOTE SHOOK

This essay is part of a slow research series, What is Research?

“Just use this time to rest,” the doctor advised me as though he was delivering good news.

Rest as a concept did not exist in my worldview. While melancholy and illness doubtlessly pranced rampantly through Appalachian Georgia’s red-clay hills where I grew up, lack defined life. Extended periods of rest without productivity were far removed from a life of dirt-under-the-fingernails. I was taught that no impairment should excuse a body from working. The catastrophically ill for whom work was no realistic option were largely reduced to taxidermy animals: lifelike, immobile, and widely understood to be expensive, useless, and resented. Most I knew spent their days inside, measuring their days in television static and soft chimes that rustle the collecting dust on a mantle clock. I later came to question these representations: as part of the problem.

At age 29, with my abdomen split open and sewn back together, I was still fundamentally uncomfortable with “rest.” Though I’m not a doctor, I knew that bodies are not supposed to open in the middle. If they do, something has gone wrong. Considering the line of precise metal staples holding the soft tissue of my guts shut, something had indeed gone wrong. In my case, the culprit was internal bleeding which gave way to near-fatal sepsis that required a majorly invasive surgery to resolve. Catastrophes of the body, as it turns out, necessitate rest.

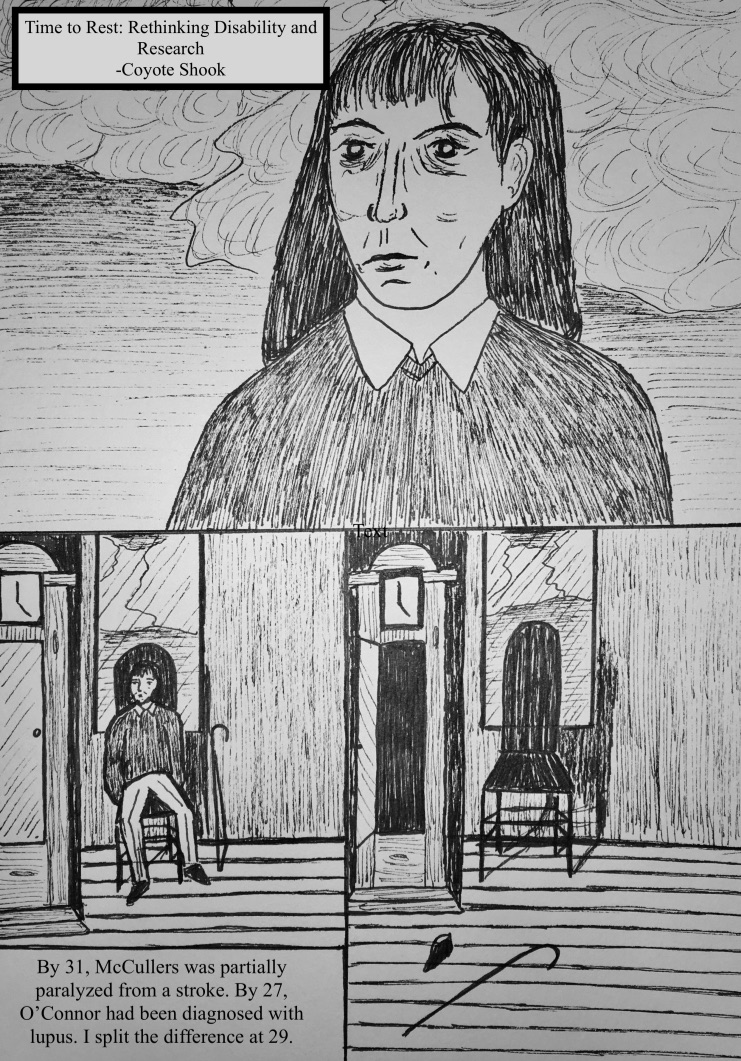

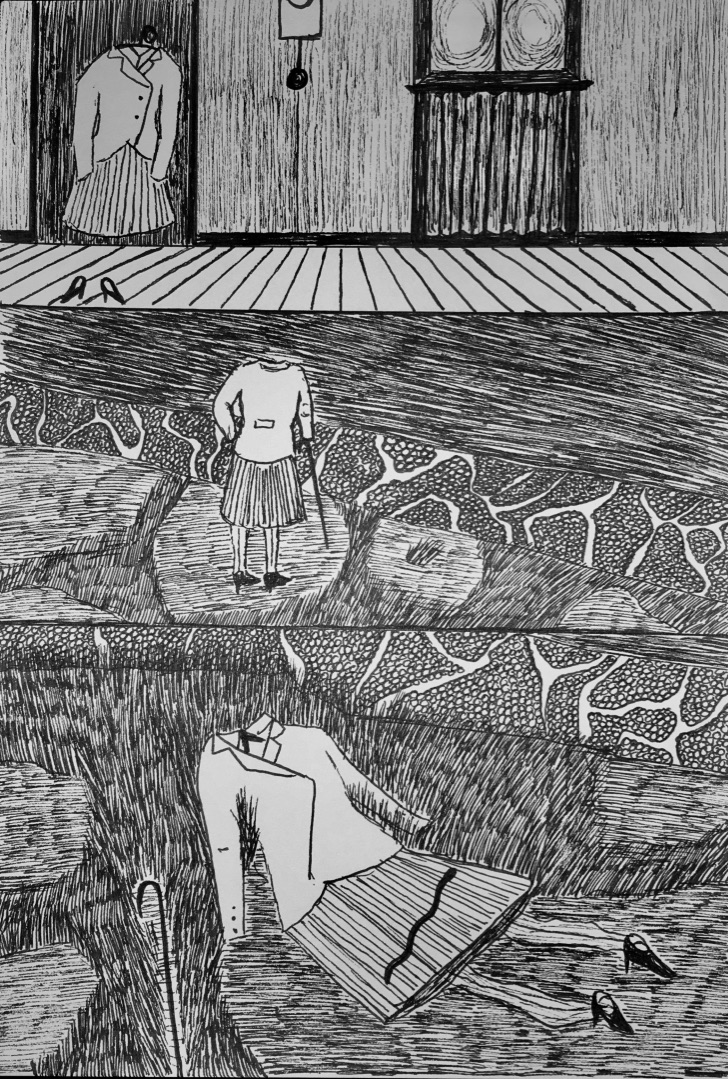

In that moment when the doctor prescribed me “rest,” my hands restrained, a breathing tube in my throat, I thought inexplicably of a comic about Carson McCullers (whose papers, personal effects, and fabulous wardrobe now call the Harry Ransom Center home) and Flannery O’Connor that sat unfinished on my desk, now doomed to indefinite incompletion for as long as “rest” took.

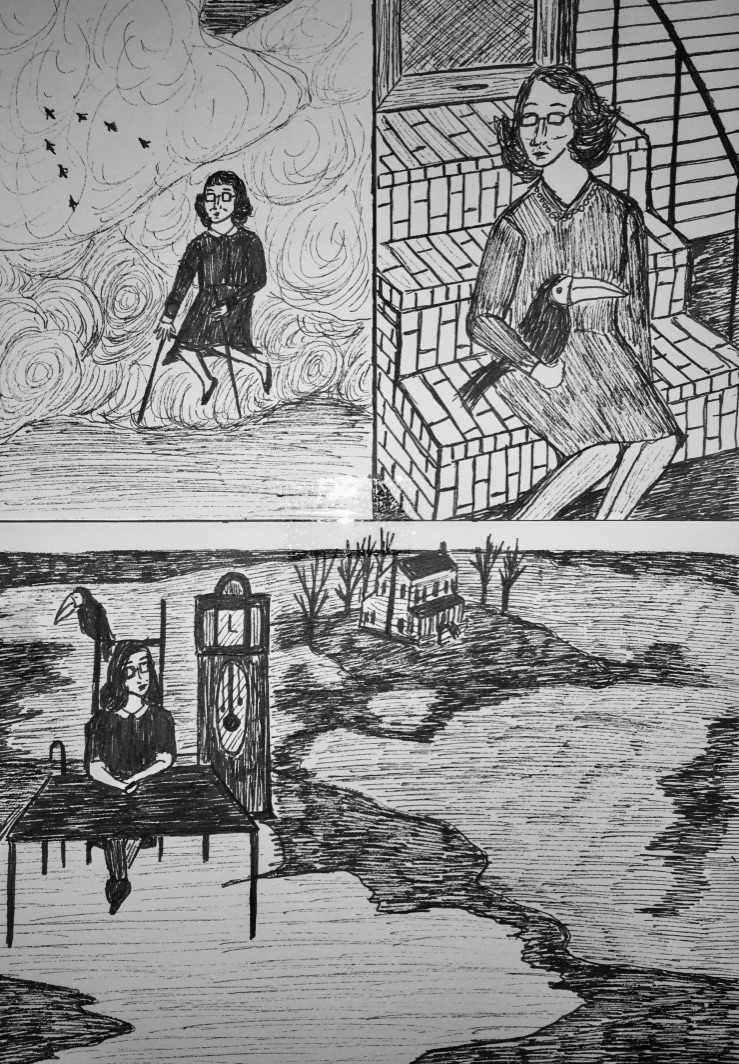

Both Georgians, both disabled and chronically ill, and both known for their caustic personalities, the two women had also doubtlessly heard similar lines about “rest” from numerous doctors in their lives. Like McCullers, I left Georgia for New York at a young age only to find my fragile health forced me to make unexpected returns to Georgia to convalesce. Like O’Connor, I too was an aspiring cartoonist who received a BA from a regional university in middle Georgia and a master’s degree from a midwestern Public Ivy. By 31, McCullers was partially paralyzed from a stroke. By 27, O’Connor had been diagnosed with lupus. I split the difference at 29. I wonder how much of their lives they spent “resting” and how much of their work sat unfinished as their bodies mended and unmended themselves.

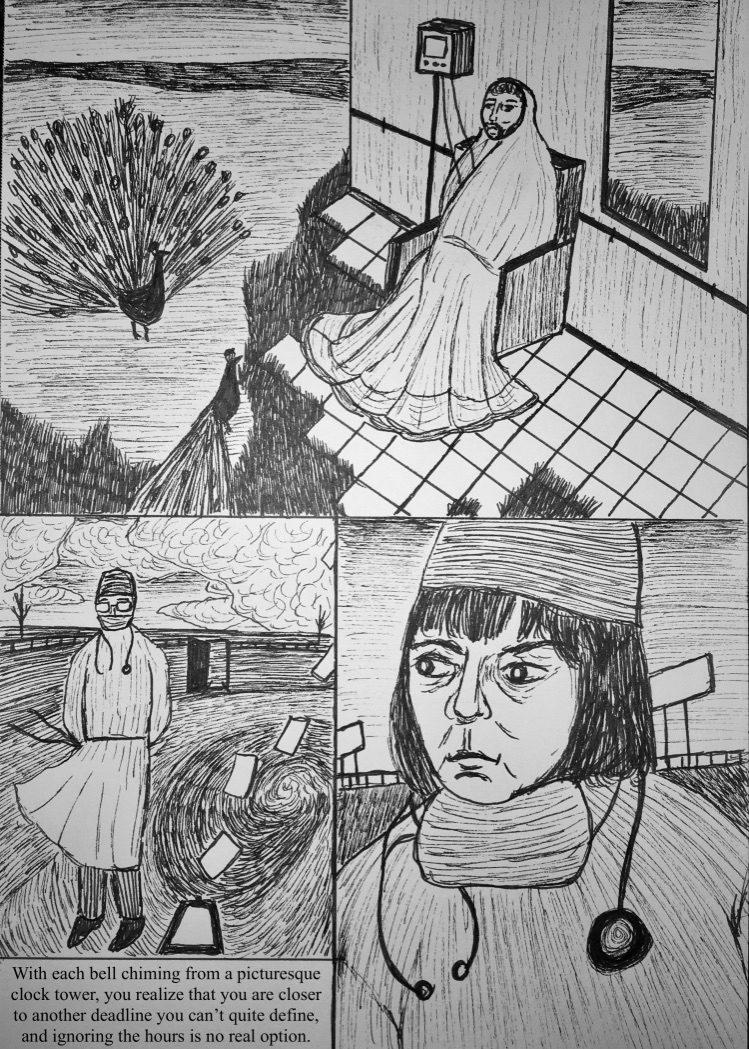

Other disability scholars such as Ellen Samuels [1] and Alison Kafer [2] have explained how disability complicates relationships with “rest” and time. With each 3 a.m. trip to radiology or vitals check, I felt another more astute expiration date marked on my body in invisible ink. My internal injuries tripled my chances of developing stomach cancer within a decade, as, the doctors warned, did my risk of death by suicide or drug addiction. However, when it came to academic research, another set of expiration dates scrambled my understanding of time more, flashing like a binary-coded clock that I was incapable of reading.

Even with tenure, extended periods of time without producing research causes evaluators to pause. For all its high-mindedness, the academy holds a similar position to my Appalachian childhood when it comes to inactivity. Productivity defines survival and dictates the amount of time you spend within the academy. From “up or out” hiring through “publish or perish,” to the daunting process of achieving tenure, one’s self-sustenance comes from output and understanding time as finite, precious, and a void to be filled at all costs with publications, fellowships, and book talks. For the chronically ill, the challenges are apparent. Substitute dirt-under-the-fingernails for printer ink, and the two world-views could walk in near-lockstep, despite their superficial differences.

Disability complicates relationships with ‘rest’ and time. With each 3 a.m. trip to radiology or vitals check, I felt another more astute expiration date marked on my body in invisible ink … When it came to academic research, another set of expiration dates scrambled my understanding of time … Extended periods of time without producing research causes evaluators to pause.

—COYOTE SHOOK

For even those in fine health, Flannery O’Connor’s Joy/ Hulga Hopewell [3] hovers like a cautionary tale: years of study can still leave you with nothing but your bitterness and a doctoral diploma sitting placidly behind the same wooden frame. For disabled aspiring academics, her prosthetic leg compounds such anxieties. With each bell chiming from a picturesque clock tower, you realize that you are closer to another deadline you can’t quite define, and ignoring the hours is no real option.

Yet other possibilities exist within rest for disability scholars. Rest itself is a transgressive research experience. As an aspiring disability scholar, I’ve found that leaning in on the academic “misbehavior of rest” and sitting with the anxiety of stillness within the framework of “publish or perish” has given my research a bitter-richness it would otherwise lack. For example, it was during such a period of “rest” where my deep disgust with hospital gowns gave me more clarity into McCullers’s penchant for her iconic jackets and suits [4], several of which I’d seen in person in the Harry Ransom Center archives. While no essay drafts or typed notes mark the time I’ve spent immobile in hospital beds, these moments are perhaps some of the most formative research experiences of my life.

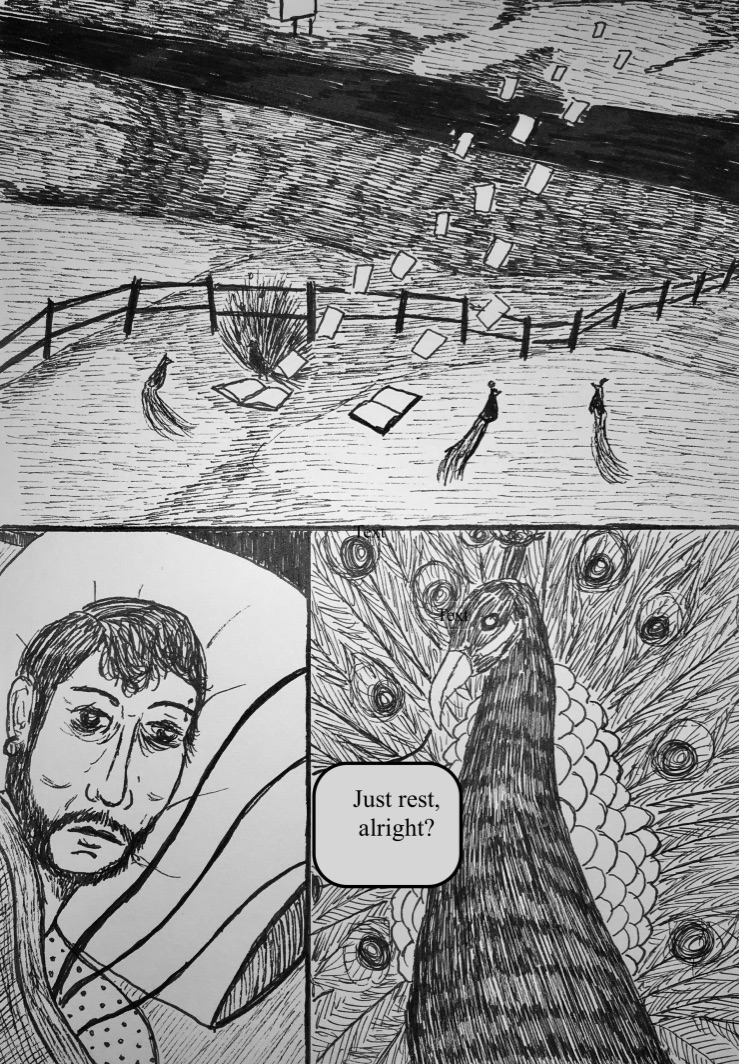

By age 50, McCullers was dead. O’Connor died at 39, spending the seven years by which she outlived her prognosis writing stories and surrounding herself with an army of peacocks on her Milledgeville farm. Would I finish my dissertation before I hit 35? How much time would I spend “on the market?” What percentage of my life would 35 years be? Or were there other questions that I and the academy hadn’t yet had the chance to ask?

“Just rest, alright?” the doctor repeats, even though the ventilator down my throat prevents me from answering. I pause for a moment, and look out the window as the sun reaches its highest point of the day, the metronome of my own heartbeat pinging in electric jolts from the monitor next to me breaking an afternoon’s silence.

[1] Ellen Samuels, “Six ways of looking at crip time,” Disability Studies Quarterly 37, no. 3 (2017).

[2] Alison Kafer, Feminist, queer, crip (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013).

[3] Flannery O’Connor, “Good Country People,” A Good Man is Hard to Find and Other Stories (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers, 1955), 169.

[4] Jennifer Shapland, “Carson McCullers, Style Icon,” Ransom Center Magazine (October 28, 2013).