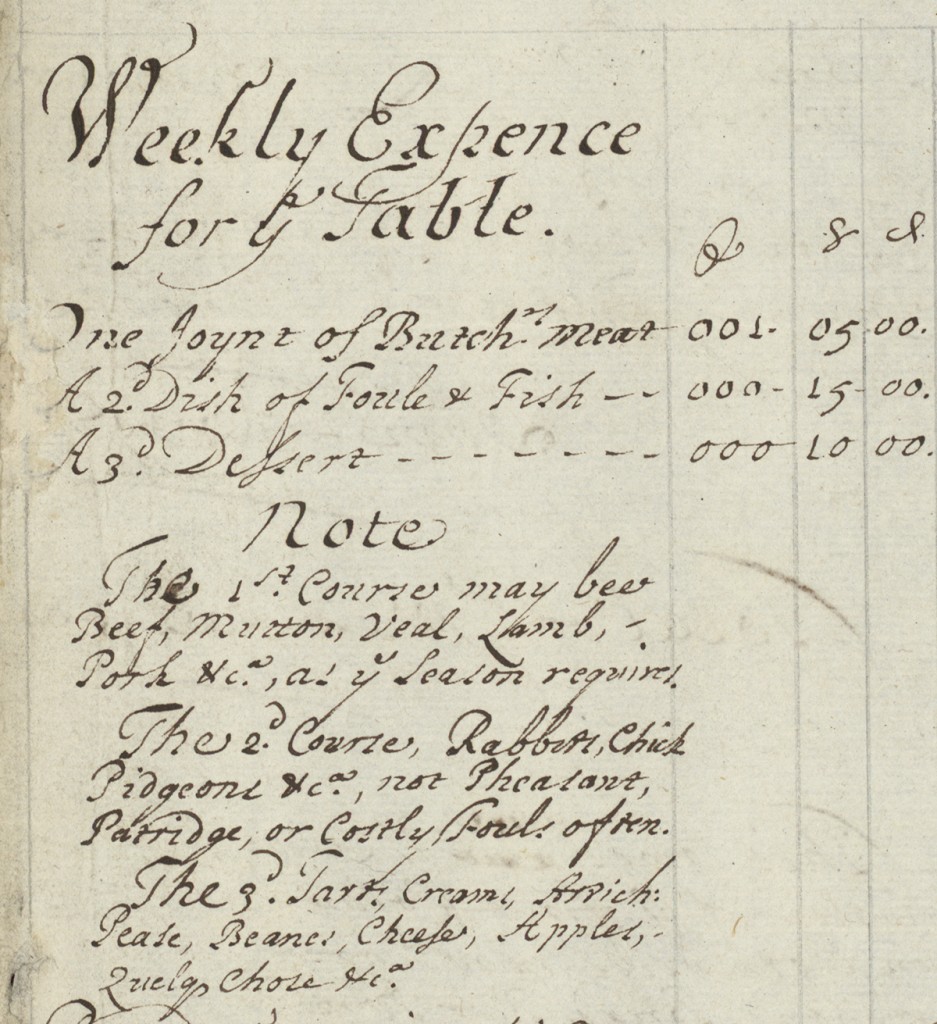

According to Mary Evelyn, the wife of John Evelyn, a renowned English intellectual, diarist, and horticulturalist in the late seventeenth century, it cost £313 and 1 shilling to set up a proper upper-class household for eight people in London in 1675. In today’s dollars, the dishes, silver, glasses, linens, and kitchen equipment required would cost approximately $62,000—without buying any furniture. It would then cost £480, 4 shillings per year (approximately $95,000/year today) to maintain and staff that house and a small, two-horse stable. This household would then have a weekly budget of £2, 13 shillings, 4 pence for meals and £4, 12 shillings, 3 pence for other household supplies like soap, candles, and fuel (approximately $1,444 today).

On her own account, this imagined household was quite frugal. Mary Evelyn wrote this set of itemized household management instructions to the Evelyns’ young family friend, the newly married Mrs. Margaret Blagge Godolphin, who was about 22 years old at the time. (The document can be viewed in full in the Ransom Center’s Carl H. Pforzheimer digital collection.) As she remarks in a short preface, Mary Evelyn provides in her accounting for “some variety, but [no] Dainties or Entertainments,” because Mrs. Godolphin has such a “just & regular life” and her husband is “so good & soe reasonable.”

Dear Child, Of ye 500 [pounds per annum]. which you tell me is what you would contract your Expenses to, and that you are to provide your Husbands Cloaths, Stable, and all other House-Expences (except his Pocket-money) I leave you 20 l. over, and for your owne Pocket [etc].40 l. (in all 60 l.) and that little enough considering Sickness, Physicians, and innumerable Accidents that are not to be provided ag[ain]st with any certainty. But (as ye Proverb you know is) I am to cut ye Cloake, according to ye Cloth; and I have done it as near as possibly I could, with some variety, but without Dainties or Entertainments; you living so just & regular a life, & having so good & soe reasonable a Husband; and I pray God to bless you both & pardon ye defects of my Obedience to your earnest Desires, who shall ever remaine,

Dear Child,

Your M.E.

April 13. 1675

While Mary Evelyn cautions her young friend that she must always be wary of surprise medical expenses that could impact her budget, she goes on to illustrate the variety of fare the Godolphins might enjoy on such a budget with a sample week-long menu of three-course meals. She summarizes these courses in a table as follows:

Additionally, Mary Evelyn provides the young Mrs. Godolphin with some very sound advice about how to pick a head housekeeper, advising the young woman to insist on firm bookkeeping practices without trying to micromanage her servants:

if you have a faithful Woman, or Housemaid it will cost you little trouble. It were necessary yt such a one were a good Market-woman, & whose Eye must bee from ye Garret to ye Cellar; nor is it enough they see all things made cleane in ye House, but set in ord.r also; That if any Good be broken or worne out they shew or bring it to her that she may see in what Condic?n it is, that nothing bee hid or imbezel’d. Use as seldom Charewomen and Out-helpers as you can they but make Gossips. She should bee ye first of servants stirring and last in bed, & have some authority over ye rest, & you must hear her and give her credit, yet not without your owne Examination & inspection, that Complaints come not to you without cause. It is necessary alsoe she should know to write and cast up small sums & bring you her Book every Saturday-night, which you may cause to be enter’d into another for your Selfe, that you may from time to time judge of Prices & things w.ch are continually altering. This Servant is to keep your Spicery, Sweet-meats Cordial waters [etc.] & ye rest of ye Servants are to account to her; & such a Server (I tell you) is a Jewel not easily to be found.

The recipient of these instructions, Margaret Blagge Godolphin, was renowned in her own time for both her beauty and religious devotion. In her teenage years, she was a Maid of Honor to the Queen in the court of Charles II. Her letters demonstrate her success at establishing a circle of admirers and friends at court, John Evelyn among them, but they also reveal an extreme frustration with the moral depravity of her fellow courtiers. She was especially impatient with her superiors’ endless card games and fashionable worldly activities that kept her from her prayers. After several years she managed to get away from the Restoration Court to serve Lady Berkeley but was soon obliged to go abroad with her while Lord Berkeley served as the English ambassador to the court of Louis XIV. From Paris, she wrote to John Evelyn of her admiration for the cloistered life of nuns even though life among Catholics exposed to her the superstitions of the Roman Church and confirmed her Protestant faith. Despite her desire to dedicate herself to a life of religious devotion after her time in Paris, John Evelyn—who had become a sort of spiritual mentor to her—persuaded her that her most pious act as a 22-year-old woman would be to follow through with a long-term engagement to be married to Lord Sidney Godolphin, the King’s Master of the Robes.

Not long after marrying, Margaret Godolphin asked the Evelyns for help with her home economics. This seven-page document thus reveals Mary Evelyn’s attempt to help her devout young friend establish a household that would provide her a refuge from the world of high society she found so tiresome. By Margaret Godolphin’s own account, it worked. She wrote of her thankfulness for the blessings she was able to enjoy after her marriage: her health, her husband, her time to herself, and her “house quiet, sweet, and pretty.” Sadly, Margaret’s enjoyment of this place of respite and meditation was cut short when she died after giving birth to her son Francis in her third year of marriage.

These household management instructions by Mary Evelyn were among Margaret Godolphin’s papers that John Evelyn set in order upon her death. Evelyn eventually turned these into a biography that remained unpublished until the nineteenth century. The Ransom Center possesses the instructions, which were enclosed in a letter sent to Samuel Pepys by Evelyn in 1685. Evelyn’s cover letter offers some humble commentary on the utility of the instructions that is tinged with regret for the loss of his dear young friend. Evelyn expresses his hope that the methodical recommendations of his wife might be helpful to other virtuous women Pepys knows. Evelyn hesitantly offers his own daughter, Susanna, as an example of such a virtuous woman who might benefit from these instructions. In parentheses, though, he adds a caveat that thinly veils a regret-filled critique of his other daughter who had recently eloped without the family’s consent and subsequently died of smallpox: “if God give her [Susanna] Grace to make a fitter Choice than her unhappy sister.” Evelyn’s rather bleak references to his own kin in this letter are strikingly juxtaposed against powerful and wistful expressions of love for Margaret Godolphin, now deceased for seven years, whom he calls “that concealed saint, and incomparable Creature, so well known to me, & my wife in particular.”

Thus, this document reveals the trust John Evelyn placed in his wife Mary’s expertise in planning, budgeting, practical math, and management skills, and provides a fascinating glimpse into the details of how a small upper-class London home operated in the late seventeenth century. Its cover letter to Pepys also provides a context that allows us to glimpse this document’s status in its afterlife as a kind of talisman that preserved for the Evelyns a tiny bit of the intimacy and spirituality of their friendship with the young Margaret Blagge Godolphin.

Transcriptions of Mary Evelyn’s Household Management Instructions are provided by Catherine Harris and Patrick Naeve, student volunteers from The University of Texas at Austin’s College of Liberal Arts Plan II Honors Program.

Please click on thumbnails below to view larger images.