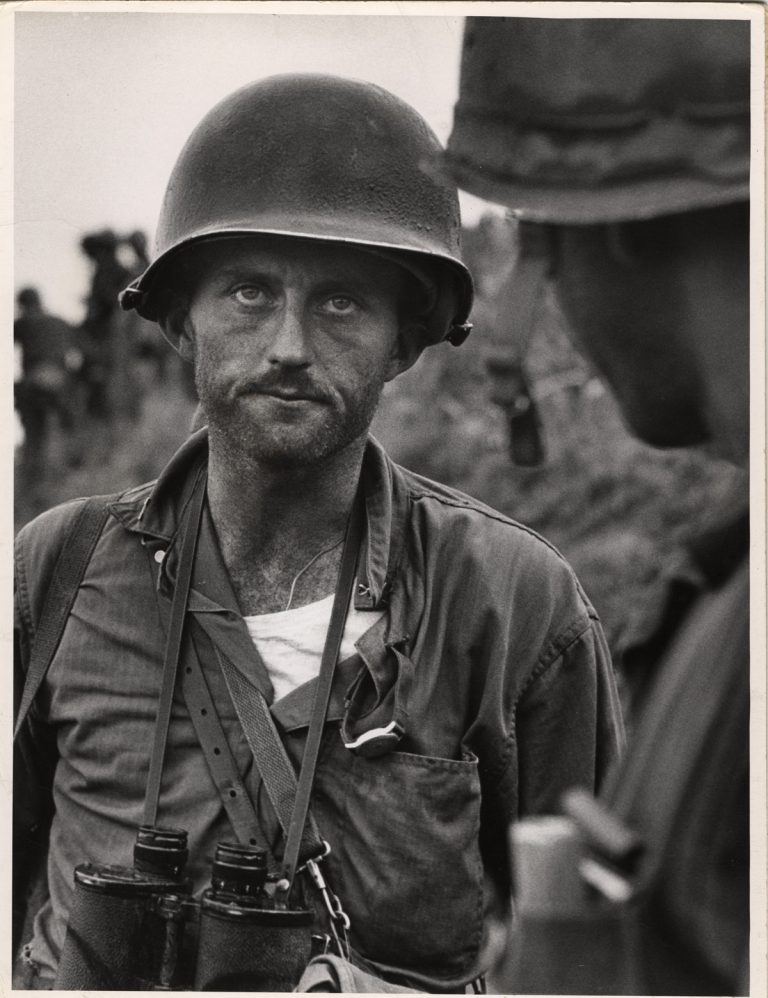

Internationally-renowned American photojournalist David Douglas Duncan celebrates his 100th birthday on January 23. For decades, Americans at home and abroad learned of world events as they unfolded before Duncan’s camera, first during his service as a combat photographer with

The Photography of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll)

On Tuesday, March 10, at 4p.m., Roy Flukinger, Senior Research Curator of Photography, speaks about the photography of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson—better known to the world as Lewis Carroll. Flukinger will discuss Dodgson’s pursuit of photography and his recognition as one of the most accomplished amateur photographers of the Victorian Era.… read more

Veterans Day conversation with photojournalist (and Marine) David Douglas Duncan

The Ransom Center holds the archive of American photojournalist and author David Douglas Duncan, including his images of World War II and the Korean and Vietnam wars. In honor of Veterans Day, Ransom Center Research Curator of Photography Roy Flukinger asked Duncan about photography, being a Marine, his experiences as… read more