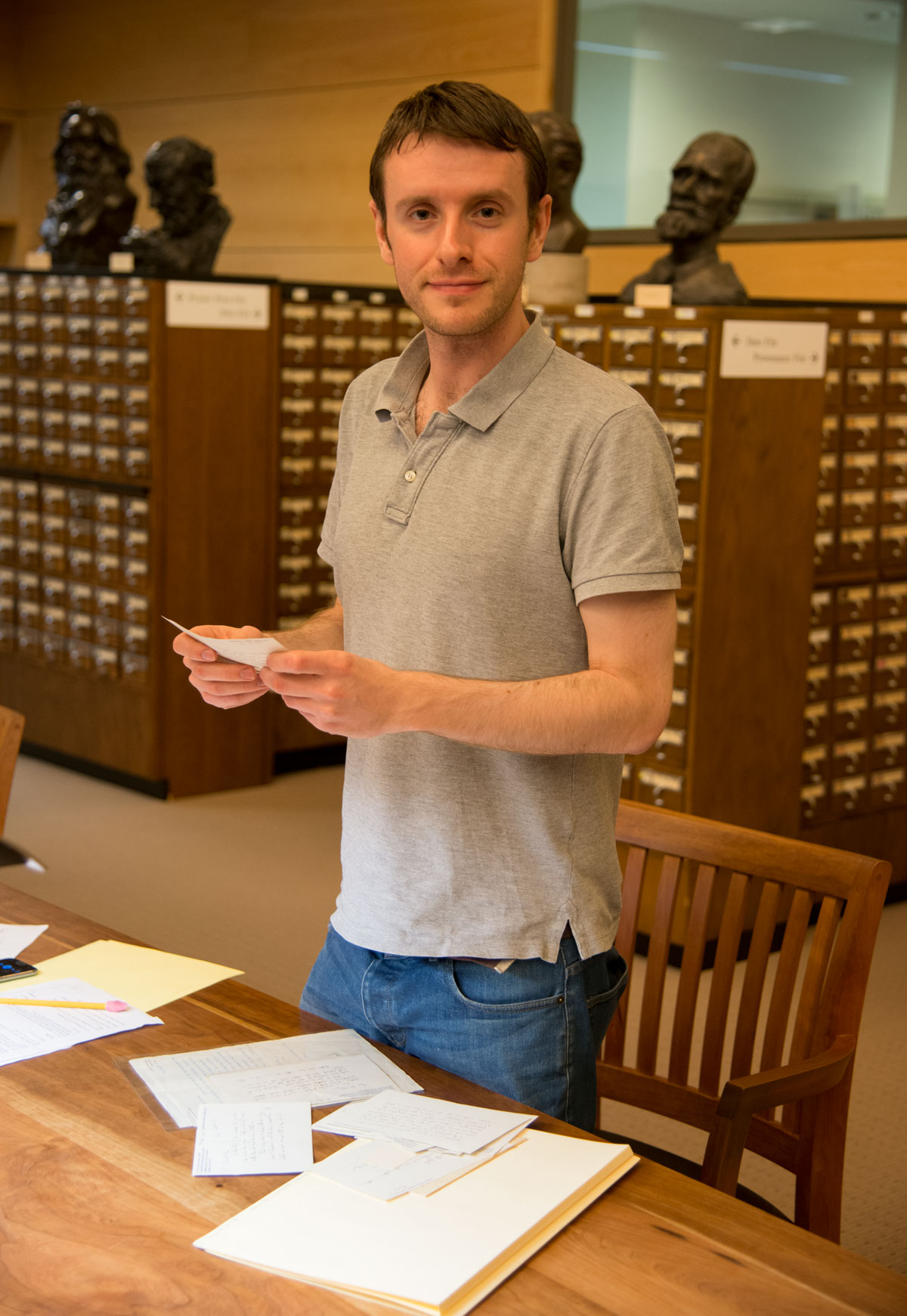

I visited the Harry Ransom Center for two weeks to access the collection of St. John Ervine (1883–1971), an enigmatic, occasionally-forgotten figure who nonetheless casts a spell over a select band of Irish scholars and historians. His personal story fuses both the culture and politics of his Ireland. [Read more…] about Fellows find: Letters of St. John Ervine, playwright for a tumultuous Ireland

George Bernard Shaw

Fellows Find: Audio interviews with British actors and actresses reveal rare insight into George Bernard Shaw productions

Jennifer Buckley, an assistant professor of rhetoric at the University of Iowa, visited the Ransom Center to work in the George Bernard Shaw collection. Her research was funded by the Limited Editions Club Endowment, and she shares some of her findings below. The Ransom Center is celebrating the 25th anniversary of its fellowship program in 2014–2015.

I came to the Ransom Center expecting to read hundreds of pages of “Shaw talk”—the lengthy, loquacious, overtly rhetorical stage speech the Irish playwright wrote for actors and readers over the course of his six-decade theatrical career.

Contemporary debates on vaccination policies have historical parallels in Ransom Center’s collections

Recently, The New York Times published an article on vaccination that has highlighted a resurging controversy. In late June 2014, a federal judge upheld a New York City policy barring unimmunized children from public schools, and objectors have decried the policy as an infringement upon their rights. In the United States, incomplete vaccination rates were highest among the poor until 1994, when the Vaccines for Children Program made it more affordable. Now, these rates are highest among the middle- and upper-classes, due to increasing philosophical and religious objections. However, such controversy is hardly new in the centuries-old history of vaccination. Documents in the Ransom Center’s collections cast historical light upon the modern vaccination debate.

In 1721 Boston, a smallpox epidemic generated an atmosphere of fear and suspicion when prominent physician Zabdiel Boylston began to counter the illness with vaccination methods. Cotton Mather, a prominent Boston clergyman, publicly declared his support of Boylston’s practices and encouraged other physicians to do the same. Outraged mobs believed vaccinators to be no better than murderers, and Boylston and Mather became subject to popular attacks, culminating in Boylston going into hiding with his family and practicing medicine in disguise. An assassination attempt made on Mather expressed the furious sentiments of the Bostonian public, as a bomb was thrown through his window with the affixed message “COTTON MATHER, You Dog, Dam you: I’ll inoculate you with this, with a Pox to you.”

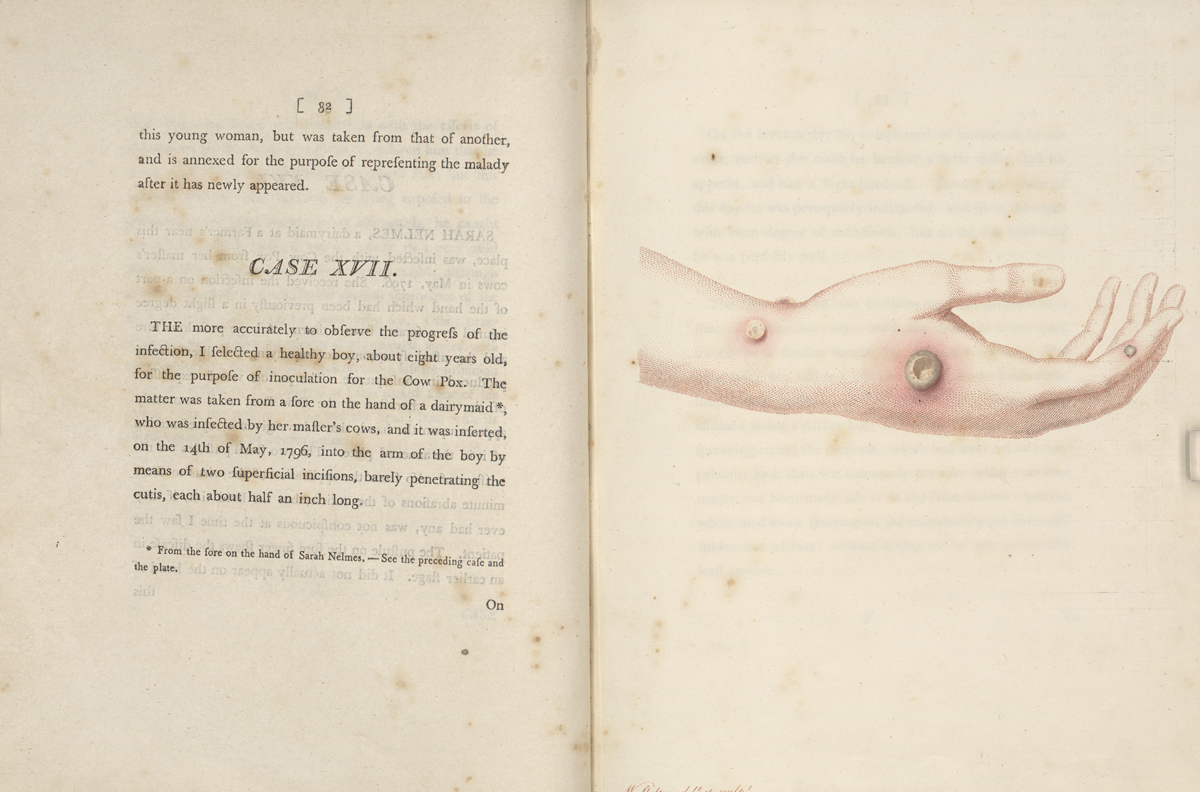

Vaccination came into more prominence and credulity with the publication of English physician Edward Jenner’s An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae in 1798. Jenner made the observation that farmhands and dairy maids, exposed to cowpox disease through their daily work, seemed to possess immunity against the more severe disease of smallpox. Jenner conducted an extensive series of cowpox inoculation case studies, often following patients for several years and even inoculating his own 11-month-old son, to see if his hypothesis about the effects of vaccination were true. Jenner’s findings increased general confidence in vaccination, as he proved that cowpox inoculations from human to human could guard against smallpox, while previously patients were more dangerously inoculated directly with the smallpox virus or from diseased animal matter.

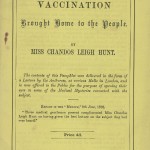

Jenner’s work contributed to the passing of the UK Vaccination Acts, key vaccination laws ranging from 1840 to 1907. The 1840 Act made vaccination free, while from 1853 to 1874 a series of more stringent acts made vaccination compulsory and even penalized objectors with fines and imprisonment. Anti-vaccination groups and protestors became more common in this period, as citizens were gripped by fears of the rumored spread of diseases such as syphilis through negligent vaccinators. Vaccination Brought Home to the People, an 1876 pamphlet by Miss Chandos Leigh Hunt, exclaims “If the devil delights in torturing, as it is represented, then indeed must he revel in Vaccination!” Pamphlets and lectures expressing such sentiments abounded as membership in anti-vaccination leagues and groups increased. A famous supporter against the UK Vaccination Acts was playwright George Bernard Shaw, who in 1906 wrote a fervent letter of support to the National Anti-Vaccination League, equating official methods of vaccination with “rubbing the contents of the dustpan into the wound.” Dissent was somewhat appeased by the Vaccination Acts of 1889–1907, which enforced regulation and safety measures for vaccination, as well as allowing for conscientious objection.

The Ransom Center also possesses many manuscripts on French scientist Louis Pasteur and his work on vaccination. Pasteur worked on a rabies vaccine from 1881 to 1885, experimenting on dogs, rabbits, apes, and eventually humans. A catalyst to his professional reputation came about in 1885, when Joseph Meister, a 9-year-old shepherd, was mauled by a rabid dog. Though Pasteur did not hold a license to practice medicine, he conferred with his colleagues about the possibility of treating the boy. His longtime friend and collaborator, physician Émile Roux, refused to work with him on the case. Finally, Pasteur found two eminent physicians who agreed to supervise the treatment. The boy recovered successfully, and Pasteur was lauded as a hero—he became nationally famous, with poets even writing odes to his genius, and went on to co-found the Pasteur Institute with Émile Roux on the laurels of his acclaimed scientific achievement.

Religious and philosophical objections have risen over the past decade, with religious exemptions for vaccinations nearly doubling in New York, and tripling in Ohio, where a measles outbreak spread throughout the Amish population. The nation has also seen a resurgence in measles and mumps, with the highest rate of measles since 1994. Debate over vaccination laws and compulsory policies in schools continues to rage, as fervent supporters arise to counter objectors in equal measure. Contemporary battles over vaccination controversy may find parallels in the past, as the centuries-old arguments and ideas resound in the modern voices of vaccination’s supporters and detractors.

Please click on the thumbnails below to view larger images.