The atria on the first floor of the Ransom Center are surrounded by windows featuring etched reproductions of images from the collections. The windows offer visitors a hint of the cultural treasures to be discovered inside. From the Outside In is a series that highlights some of these images and… read more

From the Outside In

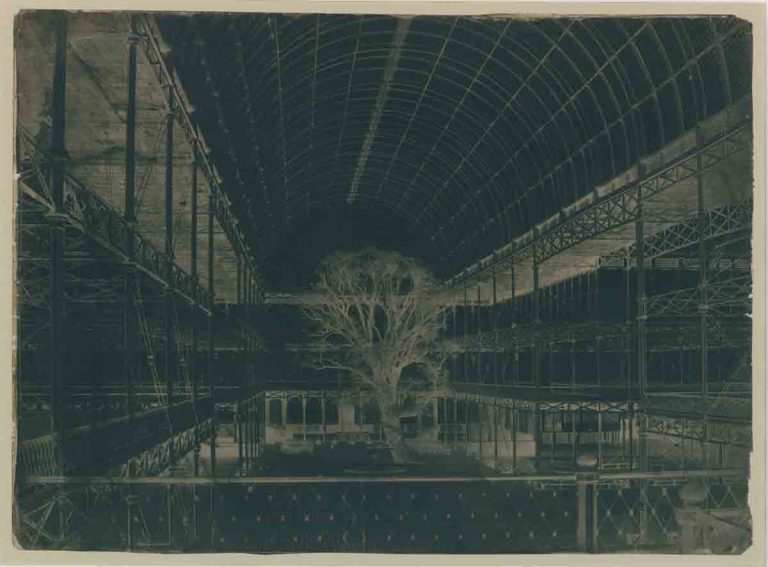

From the Outside In: “Transept of the Crystal Palace,” Benjamin Brecknell Turner, March 1852

The atria on the first floor of the Ransom Center are surrounded by windows featuring etched reproductions of images from the collections. The windows offer visitors a hint of the cultural treasures to be discovered inside. From the Outside In is a series that highlights some of these images and… read more

From the Outside In: Doodle from Notebook II of Samuel Beckett’s "Watt," 1941

The atria on the first floor of the Ransom Center are surrounded by windows featuring etched reproductions of images from the collections. The windows offer visitors a hint of the cultural treasures to be discovered inside. From the Outside In is a series that highlights some of these images and… read more