Between July 1937 and March 1938, Nonesuch Press—under the direction of George Macy—set out to publish what it billed as the most extensive collection yet made of Charles Dickens’s writings. It had already been an energetic few years. Macy founded the subscription-based Limited Editions Club in 1929, and the Heritage Press in 1935, before acquiring London-based Nonesuch Press in 1936. Nonesuch’s practice of teaming up a small hand press for design and commercial printers for production allowed for a wider circulation of its fine-press quality books. [Read more…] about George Macy’s illustrated editions of Charles Dickens’s Christmas classic

Charles Dickens

Penguin and the Paperback Revolution

Click on the four-way arrow in the bottom right-hand corner of the slideshow to convert into full-screen mode.

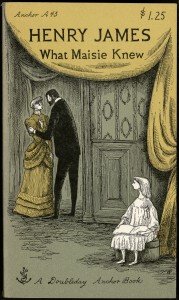

According to popular mythology, the publisher Allen Lane, founder of Penguin Books, formulated his idea for a press dedicated exclusively to paperbacks while visiting a railway station. Having spent the weekend visiting his friend Agatha Christie, the famed author of Murder on the Orient Express, Lane arrived at the Exeter railway station and realized he had forgotten his book. Frustrated and facing the boredom of a long train trip, Lane tried to buy a novel at the station but found that there was nothing available that he felt worth reading. Bookless for the next few hours, he sat on the train and planned a new line of cheap, pocket-sized, and travel-worthy books, which could be sold at railway stations, grocers, and department stores. Penguin Books—and the paperback revolution—were born.

While this version of Allen Lane’s epiphany may be slightly romanticized, there is no doubt that Penguin Books, launched in 1935, sparked a new phase of publishing that would change the printing industry irrevocably. Mass marketing of paperbacks not only brought classics to a wider audience but also brought pulp fiction—previously published in magazines—to the forefront of the book trade.

The Ransom Center’s book collection is known for first editions, many of them lush volumes with elaborate bindings. Perhaps lesser known is the fact that the Ransom Center also houses multiple volumes that illuminate the development of the paperback book trade in both America and Britain. Alongside important editions of Lane’s Penguins, the Center also houses Tauchnitz editions of paperbacks that pre-date Penguin, as well as the “penny dreadfuls” and dime novels that slowly developed into modern pulp fiction. This slideshow exhibits numerous items from the library’s collections that represent landmarks in the history of the paperback book trade.

Charles Dickens turns 200 today

Charles Dickens was born in 1812—200 years ago today—and his works continue to be some of the most beloved and enduring stories in the English literary canon. The Ransom Center has strong holdings of Charles Dickens materials, many of which were donated to the Center in the 1970s by Halstead B. Vanderpoel.

Dickens started his career as a journalist when he was 19, though he kept trying his hand at fiction on the side. He published his first story in the Monthly Magazine in December 1833 at age 21, and three years later he published his first novel, The Pickwick Papers. The book, which was published in serial form, was an enormous success in England, and Dickens went on to become the most popular writer of his time. With the serial format, Dickens could offer his novel at a low cost and enjoy a wide circulation among readers. The formula was so successful that many of Dickens’s subsequent novels were also published in serial form.

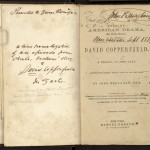

Dickens followed up success of The Pickwick Papers with Oliver Twist (1838), Nicolas Nickleby (1839), David Copperfield (1849), Bleak House (1853), Little Dorrit (1857), A Tale of Two Cities (1859), Great Expectations (1860), and other classic titles.

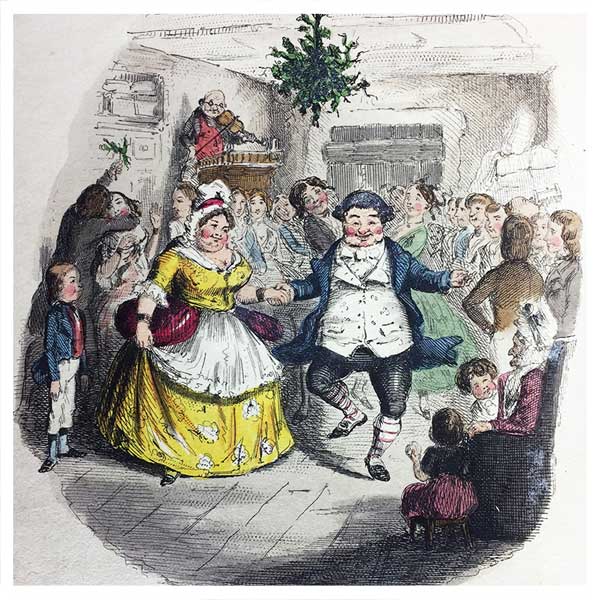

A forerunner to modern-day publishing marketers, Dickens knew how to make his works appeal to the widest possible audience. A Christmas Carol, for example, was published just in time for Christmas in 1843. Dickens wrote with humor, but he also wrote to shed light on the dark side of poverty in England at the time.

In a posthumous biography, it was revealed that Dickens came from humble beginnings. His own father was imprisoned for debt when Dickens was a child, forcing the boy and his siblings to work in a factory in terrible conditions to support the family. His experiences in the factory were later immortalized in David Copperfield and Great Expectations.

Our Mutual Friend was Dickens’s last complete novel before his death in 1870, following a 36-year career as a writer. He was working on The Mystery of Edwin Drood when he died, but he completed only six of the planned 12 installments. Dickens is buried in Westminster Abbey.

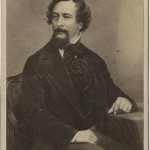

The Ransom Center’s Dickens holdings are extensive and include 168 letters, a virtually complete run of his published works, 14 books from the author’s library, and Dickens ephemera. The Charles Dickens literary file includes 39 photographs, many of which are portraits of Dickens.

The Charles Dickens art collection contains more than 1,000 paintings, drawings, prints, postcards, plates, clippings, and portfolios relating to Dickens, including original illustrations for editions of his works, renderings of fictional characters, and images of settings of his novels.

In the above slideshow, view some of the materials from the Dickens collection at the Ransom Center. Dickens’s copy of The Life of Our Lord will be on display in the exhibition The King James Bible: Its History and Influence, which opens February 28.

Please click on thumbnails for larger images.

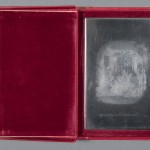

Image: Wax impression of Charles Dickens’s seal. Photo by Pete Smith.